Slavery didn’t disappear with the end of the slave trade – it currently affects more than 40 million people around the world and takes a range of forms. Slavery primarily threatens all people considered to be vulnerable, and children are unfortunately part of this group. The fight for freedom isn’t going to stop any time soon.

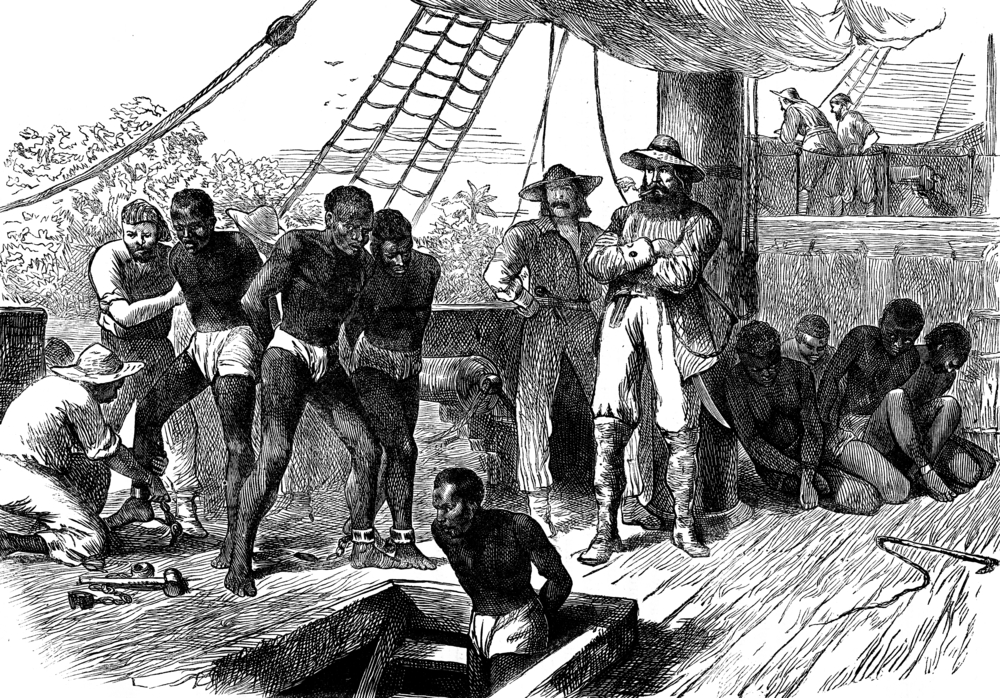

A burning sun rises, the air humid and sweltering. Suffering under the intensity of its rays, Africans – ripped from their native land – bend their backs in the sugar cane fields of the New World. That’s the image that naturally comes to mind when you hear about slavery. And the reason for that is the estimated 12-15 million Africans who were deported as part of the sugar triangle that connected Europe, Africa and the Americas (Succab-Goldman, 2011).

These men and women were exchanged for commercial goods thanks to their value as a labour force. Africans had a reputation for being better able to bear the difficult climatic conditions of the Caribbean, especially in sugar cane fields (Succab-Goldman, 2011). For practical reasons, these human beings became beasts of burden. Europeans were undoubtedly responsible for this slave trafficking, including the Swiss people who became rich from the slave trade (Pavillon, 2019), and yet African tribes were not exempt from blame, as some of them captured people from other ethnic groups to sell them to European slavers.

The French essayist and historian Tidiane Diakité, who is of Malian origin, goes so far as to say that “without the active and deliberate involvement of Africans themselves, the Atlantic slave trade would not have existed to the same extent or for the same duration” (Thibault, n.d.).

It is an age that we now consider bygone – part of the colonial past. And we think this because the exploitation of African slaves in the Americas disappeared with the rise of abolitionist movements. These were inspired and supported by Enlightenment schools of thought (Funes, 2019; Cnaudin, 2019).

Montesquieu, Rousseau and Voltaire contributed a number of satirical texts on slavery to Diderot’s Encyclopédie (Funes, 2019). Anti-slavery campaigns, bolstered by the French Revolution and by slave insurrections in the colonies (Funes, 2019) resulted in the first decrees abolishing slavery. Denmark was the first country to officially abolish the slave trade in 1792, followed by France and Great Britain in 1794 and 1807 respectively (Cnaudin, 2019).

But these were only the first steps in a long process. The reintroduction of slavery by Napoleon in 1802 (Cnaudin, 2019) and the American Civil War (1861-1865) – triggered by the slave-owning southern states’ opposition to the abolitionist northern states that supported President Lincoln (La guerre de Sécession [The American Civil War], 2017) – are proof enough of the difficulties that separate decrees from action.

These early milestones are fundamental, but they did not eradicate slavery, as it continues to exist even now in multiple forms. This fact is the very reason why the International Day for the Abolition of Slavery – marked on 2 December – exists. This day, which commemorates the United Nations General Assembly’s adoption of the Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Persons and of the Exploitation of the Prostitution of Others on 2 December 1949, has the primary aim of drawing attention to the topic and thus encouraging the fight against contemporary forms of servitude (International Day for the Abolition of Slavery, n.d.).

Today, any exploitative situation that a person is unable to refuse or leave due to threats, violence, or other forms of restrictions is considered to be slavery (International Day for the Abolition of Slavery, n.d.). Modern slavery affects over 40 million people worldwide and primarily takes the form of forced labour, debt servitude, forced marriage, human trafficking, sexual exploitation and forced recruitment of children for armed conflicts (International Day for the Abolition of Slavery, n.d.).

Above all, slavery threatens people considered to be vulnerable, whether for ethnic, social or economic reasons, but women and girls are most affected (International Day for the Abolition of Slavery, n.d.). It would be a pointless and tedious exercise to list all the attacks on freedom and dignity that slavery entail – they are so numerous. However, it is nonetheless important to denounce such practices with a quick overview. Representing a quarter of modern slaves, children are particularly affected by slavery (International Day for the Abolition of Slavery, n.d.).

Children are primarily used in agriculture, animal husbandry, forest operations and fishing (Child Labour in Agriculture, n.d.), such as the child slaves of Lake Volta in Ghana (Grandclément & Roguez, 2006). These children are under the control of their master, and very often are not able to flee. This forced labour is generally accompanied by mistreatment such as lack of food and sleep as well as corporal punishment (Grandclément & Roguez, 2006). But it is also possible to be born a slave.

In Afghanistan, entire families can be reduced to slavery because of a vicious cycle of debt (Mathieux, 2014). Children and parents alike perform back-breaking labour such as brick-making, 11 hours a day, six days a week, and are entirely resigned to doing so (Mathieux, 2014). Slavery becomes a yoke passed down from generation to generation. All over the world, there is no lower age limit for child slaves, who are sometimes put to work from as young as three years old (Mathieux, 2014).

Children are not only used as unskilled labour but are also essential assets for dangerous work such as illegal mining operations, whether in underground pools in Africa (Charbit, 2019) or in narrow wells in underwater mines in the Philippines (Human Rights Watch, 2015). In some conflicts, children are forcibly recruited by government armies or rebel groups as fighters, cooks or messengers (Enfants soldats [Child soldiers], n.d.).

Although they take part in the conflict, the people commonly referred to as child soldiers are victims first and foremost as they are forced to act against their will (Enfants soldats, n.d.). Living in a violent environment, they are reduced to servitude and are abused and exploited – when they are not killed (Enfants soldats, n.d.). According to Unicef, 250,000 children worldwide are victims of such a situation (Unicef France, 2012).

Girls, while also at risk of the same treatment as boys, are exposed to other types of slavery. Forced marriage often makes girls their husbands’ slaves. In Nigeria, girls aged 12-13 are sold by their mothers for around €100 to middle-aged men (Herz, 2019). In many cases, the young bride is raped and assaulted and becomes her husband’s domestic slave (Herz, 2019). Furthermore, women and girls are particularly affected by sexual exploitation; they represent 99% of victims of the sex ‘industry’ (International Day for the Abolition of Slavery, n.d.).

In addition, the violence that women living in slavery face can be extreme, even in agriculture. In India, it was recently discovered that sugar cane producers force a proportion of their workforce to undergo hysterectomies (Menon, 2019). By preventing their employees from becoming pregnant, the landowner then sees a productivity gain. It is clear that women are still all too often reduced to sexual property or machinery.

While we tend to talk about what happens in developing countries that experience high levels of social inequality, slavery is also present in European societies. In fact, we’re involved in slavery around the world through the purchases we make (RTS, 2012). One approach is to boycott products manufactured using slavery, which puts pressure on multinationals (RTS, 2012).

However, a mass boycott could have harmful consequences, particularly on the children who would lose their job, would no longer be able to help their family survive, and would run the risk of finding themselves in vulnerable situations that push them to accept more dangerous and even less regulated work (RTS, 2012). But how can this scourge be brought to an end?

Firstly, by remembering that the root cause of slavery is not globalisation but poverty (RTS, 2012). Secondly, multinationals are anything but the only parties responsible for slavery. Government involvement in the fight against slavery is reducing, leading private organisations to take up the slack (RTS, 2012).

The United Nations, the International Labour Organization (ILO), the World Health Organization (WHO), Unicef and a number of other NGOs have set themselves the task of working to eradicate forced labour (RTS, 2012). The Fair Labour Association performs investigations and tracks commercial goods with the aim of finding out who produces them and under what conditions, and then creates corrective action plans (RTS, 2012).

The organisation works with companies and agricultural producers to improve their efficiency and their yield, thus avoiding the negative economic impact of transitioning to work that respects human rights (RTS, 2012). In particular, it strives to remove children from work, enable them to receive an education, and improve their families’ socioeconomic situation (RTS, 2012).

Humanium, which works to ensure that children’s rights are recognised and respected, is also involved in efforts to combat child labour, in particular by promoting education and creating rehabilitation centres for child labourers (India). However, while the reduction in child labour in industry and factories is welcome, it persists in agriculture and mining.

Throughout history, there have been slaves in some form of servitude. Humans, not content simply to own property, are tempted to expand their ownership to cover their fellow people. While socioeconomic conditions may encourage servitude, it is important not to forget that human nature is at the root of all abuses. Underneath the concrete action that is being taken, it is ultimately a revolution within humanity itself that is taking place.

Projects run by Humanium: https://www.humanium.org/en/projects-3/

Support Humanium’s activities: https://www.humanium.org/en/donation/

Sponsor a child: https://www.humanium.org/en/child-sponsorship/

Become a member: https://www.humanium.org/en/participate/member/

Written by Alexis Baron

Translated by Garen Gent-Randall

Proofread by Alexandria Harris

Bibliography

Charbit, Y. (2019, 4 September). L’exploitation des enfants dans les mines aujourd’hui. Accessed on 8 November 2019 from Bon pour la tête: https://bonpourlatete.com/actuel/l-exploitation-des-enfants-dans-les-mines-aujourd-hui

Child Labour in Agriculture. (n.d.). Accessed on 8 November 2019, from the Food and Agriculture Organization: http://www.fao.org/childlabouragriculture/en/

Cnaudin. (2019, 27 April). L’abolition de l’esclavage en France et dans le monde. Accessed on 6 November 2019 from Histoire pour Tous: https://www.histoire-pour-tous.fr/dossiers/4118-labolition-de-lesclavage-et-de-la-traite.html

Enfants soldats. [Child soldiers.] (n.d.). Accessed on 13 November 2019 from Unicef: https://www.unicef.fr/dossier/enfants-soldats

Frère, C. (2018, 17 May). Les Vidomégons du Bénin, une enfance bafouée. Accessed on 8 November 2019 from La Libre Afrique: https://afrique.lalibre.be/19209/les-vidomegons-du-benin-une-enfance-bafouee/

Funes, N. (2019, 4 February). Comment la France a aboli une première fois l’esclavage. Accessed on 6 November 2019 from L’OBS: https://www.nouvelobs.com/histoire/20190204.OBS9565/comment-la-france-a-aboli-une-premiere-fois-l-esclavage.html

Grandclément, D., & Roguez, J. (2006). Les petits esclaves du lac Volta – Thalassa. Accessed on 8 November 2019 from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b8PAjG8RU9Y

Herz, V. (2019, 6 September). Nigeria : l’esclavage des jeunes filles, sous couvert de “Money Marriage”. Accessed on 14 November 2019 from France24: https://www.france24.com/fr/20190906-actuelles-nigeria-money-marriage-esclavage-filles-france-viols-histoire-famille-bolivie-fem

Human Rights Watch. (2015, 29 September). Philippines: Children risk death for gold. Accessed on 8 November 2019 from Human Rights Watch: https://www.hrw.org/video-photos/video/2015/09/29/philippines-children-risk-death-gold

International Day for the Abolition of Slavery. (n.d.). Accessed on 7 November 2019 from the United Nations: https://www.un.org/en/events/slaveryabolitionday/background.shtml

La guerre de Sécession. (2017, 6 June). Accessed on 7 November 2019 from L’Histoire: https://www.lhistoire.fr/carte/la-guerre-de-s%C3%A9cession-1861-1865

Mathieux, L. (2014, 6 January). Reportage – Afghanistan. Accessed on 8 November 2019 from Libération: https://www.liberation.fr/planete/2014/01/06/je-ferai-des-briques-toute-ma-vie_970919

Menon, M. (2019, 18 June). Violences faites aux femmes. En Inde, des ablations de l’utérus forcées. (Firstpost-Bombay, publisher) Accessed on 14 November 2019 from Courrier International: https://www.courrierinternational.com/article/violences-faites-aux-femmes-en-inde-des-ablations-de-luterus-forcees

Pavillon, O. (2019, January). Des Suisses au coeur de la traite négrière. Passé Simple – Mensuel romand d’histoire et d’archéologie(41). Accessed on 6 November 2019

RTS. (2012, 27 May). Géopolitis. Esclavage des enfants: comment y mettre fin? Accessed on 14 November 2019 from https://pages.rts.ch/emissions/geopolitis/3929732-esclavage-des-enfants-comment-y-mettre-fin-.html

Succab-Goldman, C. (2011). Une histoire de l’outre-mer. France. Accessed on 6 November 2019 from https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x2b8sl9

Thibault. (n.d.). Les partenaires africains de la traite négrière atlantique. Accessed on 6 November 2019 from Philisto: https://www.philisto.fr/article-92-partenaires-africains-de-traite-negriere-atlantique.html

Unicef France. (2012). Child soldiers. Accessed on 13 November 2019