Children of Kiribati

Realizing Children’s Rights in Kiribati

Culturally, Kiribati children are at the heart of Kiribati society. However, they remain vulnerable and risk losing their rights, most of all because prostitution is on the rise.

Population: 103.000 Life expectancy: 68,9 years |

Main problems faced by children in Kiribati:

Birth registration fees are free for the first three months after the baby’s birth.

However, this legislation is not always implemented. Fees are charged if babies are registered 10 days after birth and there is also a charge for birth certificates.

As a result, many children are unregistered and thus invisible as far as society is concerned, putting them at greater risk of discrimination, negligence, exploitation and abuse, often of a sexual nature.

In 2009 the mortality rate of children less than five years old was 46%. Consequently, Kiribati is 61st from the bottom in human development rankings (129th in the world rankings).

In addition, UNICEF statistics show that the percentage of newborns with a low birth weight increased fivefold between 2005 and 2009. Rural populations are more affected than their urban counterparts.

Thus, Kiribati is ranked 129th in human development ratings.

In March 2012, the UN Development Programme estimated that Kiribati was capable of reducing its infant mortality rate and improving mothers’ health, and would ultimately be able to reach the Millennium Development Goals.

Kiribati children are also affected by health problems (respiratory diseases, diarrhoea, anaemia and obesity) linked to malnutrition and sugary diets.

STDs such as AIDS are also on the rise.

Lack of access to drinking water and clean toilets also poses a risk to children’s health; UNICEF studies reveal that, in some areas, water contains a strong concentration of nitrates. Nitrates cause illness and, most significantly, brain problems in children.

Access to schools is free and education is compulsory for all children between 6 and 14 years of age.

Access to schools is free and education is compulsory for all children between 6 and 14 years of age.

In 1999, 99.5% of Kiribati children went to primary school. The boy/girl ratio was almost equal at primary level, but girls outnumber boys at college and secondary level.

In spite of government policy, which allocates almost a fifth of its budget to education, there are still significant problems with teaching quality, school accessibility for rural children, teaching costs, not to mention the lack of qualified teachers.

The difference between the most remote areas of Kiribati and the schools in South Tarawa leads many families to send their children away for their secondary studies. Thus, the schools in South Tarawa are often oversubscribed – with some schools responsible for over 1000 pupils.

In addition, schools are less and less safe for children as they are further and further away from their parents. Children are victim to severe bullying, harassment, including sexual harassment, and commercial exploitation, often leading to pupils truanting.

Environment

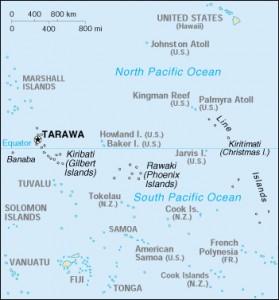

Since it comprises 33 atolls, Kiribati is directly affected by global warming.

Since it comprises 33 atolls, Kiribati is directly affected by global warming.

Rising water levels pose a very real threat to children’s living conditions and food provision. Already, children see their houses deteriorating before their eyes or are forced to leave home to escape flooding. At the last Doha conference, the Kiribati president, Anote Tong, said ‘…communities ….will have to be moved because their villages are underwater.’ He claimed that more rising sea levels are to come and announced ‘in Kiribati we don’t talk about economic growth or standard or living. We talk about survival’ before adding ‘[their] days are numbered’.

Kiribati is negotiating with the Fiji isles, with the aim of buying several hectares of land; the hope is that some of the Kiribati population will be transported there.

The state allocates a large proportion of its resources to these negotiations to the detriment of public health policies and spending on food and education.

Similarly, the Republic of Kiribati has created the largest natural marine reserve in the world, the PIPA (Phoenix Islands Protected Area – approximately the size of California), to protect its sea life and conserve its natural habitat. This reserve has been listed as a world heritage site by UNESCO since 2010.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b6DpVzRU1Iw&feature=player_embedded

In Kiribati, children under the age of 14 do not have the right to work ( part 9, section 84 of the Employment Law, Employment of Children and Other Young People) and children under the age of 16 are not allowed to work in the industrial sector or on board ships. The Constitution also outlaws forced labour.

But with 98,000 inhabitants, 50% of whom are children, and a gross national income of $1890 per head, children are often forced to work to subsidise the needs of their families.

Thus, many children under the age of 14 are unofficially employed in less formally managed economic sectors, either full time or outside school hours. They may, for example, sell brooms, combs, flowers or other small items on the street.

Although Kiribati children do not appear to be targeted by child trafficking, the law does not offer any protection; child trafficking is not illegal.

Domestic violence is frequent and is accepted by communities. Much child violence is worsened by alcohol as well as economic pressures within the family.

Domestic violence is all the more worrying for children because the ‘rule of silence’ operating within communities allows violence to pass unopposed; actions are rarely held up to scrutiny.

In addition, police report more and more young people attacking members of their family under the influence of alcohol; girls are frequently the victims of this behaviour.

Although usually avoided, child rape is a traditional form of punishment. For the most part, children are raped by a family member or someone known to the victim. This has disastrous consequences for the child because as soon as she loses her virginity, the community considers her ‘damaged goods’. Girls may also have scars on their face to signify to the community that they are no longer virgins.

Prostitution and sexual exploitation

Coercing children under the age of 15 into sexual intercourse carries a sentence of 2 years in prison under criminal law, which also forbids parents and guardians from prostituting children under the age of 15.

Many girls are victims of sexual exploitation by members of their own family and community.

In 2000, 80 young ‘te korekorea’ (sex workers linked to foreign fishing vessels which moor in Kiribati) went to visit boats in the harbour often in exchange for money, clothing and fish. Some of these workers were as young as 14. They put themselves at risk of sexual diseases as a result of unprotected sex.

Prostitution occurs because of the low, unprotected status of women and children, the lack of education, the rate of unemployment, poor legislation and poverty.

These young girls are part of a system which feeds whole families and sometimes leads to girls being forced into prostitution.

In Kiribati, girls are still less well-educated than their male counterparts even though times have changed, notably since the UN resolution in 2006. The divide between girls and boys has been all but eradicated at primary and secondary level.

Moreover, girls outnumber boys at sixth form level and in alternative training.

However, discrimination is still in evidence: girls and adolescents who are the victim of rape or incest, and who, as a result, have lost their virginity, are not accepted by many schools. These girls find themselves excluded from the education system and stigmatised by society.

Children from poor families continue to be victims of discrimination as a result of the cost of education, the lack of infrastructure in isolated areas and teaching disparities at nursery level.

23% of the 3,840 surveyed disabled people are less than 20 years old. (2003-2005 survey. Disabled children are culturally accepted, and families make it their duty to provide a loving, secure environment for all their children.

Discrimination against mentally or physically disabled children is also outlawed by the Constitution.

However, disabled children are discriminated against in other ways, since very few resources are actually allocated to such children. Only one school in South Tarawa, funded by the Red Cross, caters for the disabled. This school accepts children of all ages with all sorts of disabilities but is managed by teachers without any specific training.

Moreover, the admission criteria for wheelchair users are based on their weight and mobility: if the child is too heavy to be lifted onto the bus, the child cannot come to school because the buses are not equipped with any mechanical system to load wheelchairs.

It is actually a breach of children’s rights to be denied access to schools because of a disability, as set out in article 23 of the International Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Despite a lack of resources and funding, the government is committed to implementing policies for the disabled; it hopes to bring the country in line with article 23 of the Children’s rights convention.

Child pornography

Child pornography is not yet an offence. Thus, it is freely available on video and online.

Sixteen is the legal age for marriage.

However, for cultural reasons, parents, family members or village chiefs working for families arrange marriages for children as young as 13.

Marriage is also an underhanded way of selling children to subsidise the needs of the rest of the family.

Adoption

Children are not fully protected by adoption laws and risk being unofficially adopted, as is the Kiribatian tradition, and shared by other families. A legal adoption can be rescinded if there is evidence that the child is not attached or attentive enough to his/her adoptive parents or grandparents. All is left to the discretion of the magistrate.

81% of children aged between 2 and 14 were subject to some form of physical punishment between 2005 and 2006.

In Kiribati culture, children must respect and obey their elders from a young age.

Although criminal courts forbid cruelty to children, it allows ‘reasonable punishment’ (article 226)

Physical punishment is legal in the home, as well as in foster homes and children’s homes. It has been illegal in schools since 1997 (Education Amendment of 1997 and the 1997 Education Law). However, it is not illegal in criminal law.

Corporal punishment can also be applied as a sentence. Nevertheless, in practice, it is rarely prescribed by magistrates. Legal disciplinary measures also exist in prisons.

Criminal law in Kiribati has no real provision for children. Thus, 16-18 year olds are detained alongside adults.

There is also no alternative to prisons for young offenders; significantly, this contravenes article 40 of the International Convention on the Rights of the Child.