Fifteen percent of the world’s population – at least one billion people – have some form of disability, whether present at birth or acquired later in life. Moreover, children with disabilities, which account for 240 million of all disabled people globally, are among the most marginalized people in every society. Their invisibility is also a key factor in their exposure to violence and violations of their rights. Nevertheless, there can come about a shift in perspective. Instead of focusing on what children with disabilities lack, “diversability” proposes a counter narrative which strengthens their abilities instead of their lacks.

Definition of disability

According to the Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (CRPD), children with disabilities “include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory impairments, which in interaction with various barriers, may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis” (UN DESA, 2023). Children and adolescents with disabilities are a highly diverse group with wide-ranging life experiences (UNICEF, 2023).

They include children who were born with a genetic condition that affects their physical, mental, or social development; those who sustained a serious injury, nutritional deficiency, or infection that resulted in long-term functional consequences; or those exposed to environmental toxins that resulted in developmental delays or learning disabilities. On a mental and emotional level, disability can also be understood as those who developed anxiety or depression as a result of stressful life events (UN DESA, 2023).

Disabilities around the world

Discrimination against children with disabilities has existed in every community throughout history, and it assumes specific features according to the geographical and cultural context in which discrimination against children with disabilities takes place. For instance, traditional Confucian beliefs see the birth of a child with a developmental disability as a punishment for parental violations of traditional teachings, such as dishonesty or misconduct. Along similar lines, individuals from South-East Asian cultures may believe that developmental disabilities are caused by “mistakes” made by parents or ancestors.

Some other cultures in India offer multiple causes for a disability, ranging from medicines or illness during pregnancy and consanguinity, to psychological trauma in the mother and lack of stimulation for the infant. Finally, in other cultures, the will of God or Allah, karma, evil spirits, black magic or punishment for sins may be seen as causes of disability whereas in some others traditional beliefs are combined with biological models such as disease degeneration and dysfunction (Otufat-Shamsi, 2015).

Children with disabilities in numbers

It is estimated that nearly 240 million children have some form of a disability (UNICEF, 2023). This estimate is based on a more meaningful and inclusive understanding of disability, which considers several domains of functioning, including those related to psychosocial well-being (UN DESA, 2023).

According to UNICEF, 1 in 10 of all children worldwide has a disability. In particular, West and Central Africa records the highest percentage of children aged 0 to 17 years with disabilities (15 percent), followed by Middle East and North Africa (13 percent), and South Asia (11 percent). The American continent records an average of 10 percent, as well as Eastern and Southern Africa, whereas Europe and Central Africa mark a significant improvement, reaching 6 percent (UNICEF, 2021).

Legislative framework protecting children with disabilities

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) recognizes the human rights of all children, including those with disabilities (UN DESA, 2023). In particular, the CRC introduces specific rights for children with disabilities for the first time in international human rights law. For instance, Article 2, which deals with the right to non-discrimination, includes disability as a specific ground for protection against discrimination, and Article 23 explicitly addresses the situation of children with disabilities (Save the Children, 2009).

Along with the CRC, the Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (CRPD) provides a powerful new impetus to promote the human rights of all children with disabilities. It was adopted in 2006 in response to the severe human rights violations experienced by people with disabilities worldwide and marked a significant shift in perspective.

Instead of viewing people with disabilities as “objects” of charity, medical treatment, and social protection, it adopts the idea that people with disabilities are “subjects” with rights who are capable of claiming those rights and making decisions for their lives based on their free and informed consent as well as being active members of society (UN DESA, 2023).

The CRPD obligates governments to take concrete measures to promote full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms of children with disabilities (UNICEF, 2023). In particular, Article 7 requires States parties to take all necessary measures to ensure the full enjoyment by children with disabilities of all human rights and fundamental freedoms on an equal basis with other children (principle of non-discrimination). Moreover, it reaffirms the principle of the best interest of the child as a primary consideration in all matters affecting the child.

Moreover, it states that children with disabilities have the right to express their views freely on all matters affecting them, and that their views will be given due weight in accordance with their age and maturity on an equal basis with other children, and that children will be provided with disability and age-appropriate assistance to realize that right (Article 7, 2023).

Finally, in 2006, the Committee of the Rights of the Child agreed to produce a General Comment on Children with Disabilities, which is meant to provide guidance and assistance to States parties in their efforts to implement the rights of children with disabilities, in a comprehensive manner which covers all the provisions of the CRC (General Comment No. 9, 2006). A draft produced by the Committee in 2006 was discussed in August 2006 at a meeting in New York of up to 40 representatives from disability organisations, before being finalised and adopted by the Committee in 2007 (Save the Children, 2009).

The risks linked to disability

The marginalization and invisibility are also key factors for children’s exposure to rights violations (UNICEF, 2021). Rates of early death for children with disabilities may be as high as 80 percent in countries where mortality rates for under-fives as a whole have decreased below 20 percent (Save the Children, 2009).

According to UNICEF, compared to those without disabilities, children with disabilities are more likely to stunted (34 percent) or wasted (25 percent), they are 25 percent less likely to attend early childhood education or to have foundational reading and numeracy skills (42 percent) and 49 percent are more likely to have never attended school. Regarding children’s protection against violence, 32 percent are more likely to experience severe corporal punishment. Finally, more than a half are more likely to feel unhappy (51 percent) or discriminated against (41 percent) (UNICEF, 2023).

Discrimination against children with disabilities

Despite advancements in legislation, children with disabilities are among the most marginalized globally (UNICEF, 2023). Sometimes they also suffer from intersectional discrimination. Worldwide, this is especially the case for girls; children who are poor, Black, Indigenous, or LGBTQI+; and those who belong to ethnic minorities, migrant communities or other marginalized groups (UNICEF, 2023).

Moreover, a wide range of barriers limits their ability to function in daily life, access social services (like education and health care) and engage in their communities. These include:

- Physical barriers – for example, buildings, transportation, toilets and playgrounds that cannot be accessed by wheelchair users;

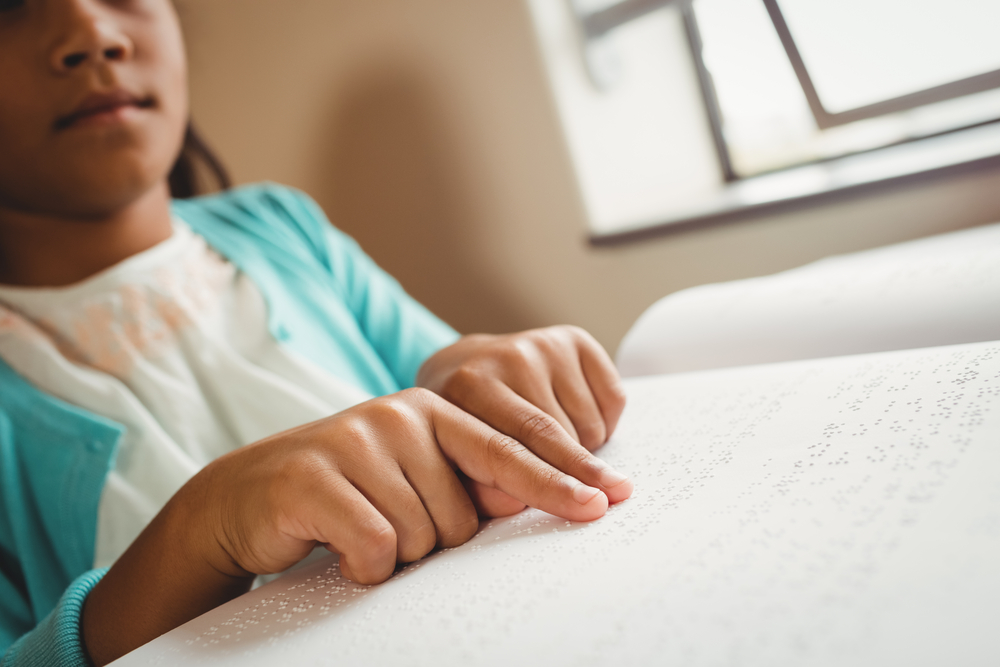

- Communication and information barriers – such as textbooks unavailable in Braille, or public health announcements delivered without sign language interpretation;

- Attitudinal barriers – this includes stereotyping, low expectations, pity, condescension, harassment and bullying.

Each of these is rooted in stigma and discrimination that reflect negative perceptions of disability associated with ableism: a system of beliefs, norms and practices that devalues people with disabilities (UNICEF, 2023). In this sense, children with disabilities are not valued the same as other children, and are widely seen as either incapable or in need of love, affection, humour, friendship, cultural and artistic expression and intellectual stimulus. They risk being segregated, marginalised and isolated, and they are exposed to higher risks compared to their peers without disabilities.

Violence against children with disabilities

When it comes to protection against violence, children with disabilities are at a dramatically heightened risk of violence, neglect, abuse and exploitation. In spite of limited data and research, available studies reveal an alarming prevalence of violence against children with disabilities – from higher vulnerability to physical and emotional violence when they are young to greater risks of sexual violence as they reach puberty.

Indeed, children and adolescents with disabilities are 3 to 4 times more likely to experience physical and sexual violence and neglect than other children; and they are at significantly increased risk of experiencing sexual violence: up to 68 percent of girls and 30 percent of boys with intellectual or developmental disabilities will be sexually abused before reaching their 18th birthday (UN Violence against children, 2023).

Moreover, incidents of violence reported by children with disabilities are largely dismissed, as their caregivers are often unprepared and ill-trained to consider the complaints and to effectively take them into account. This is a direct consequence of the current perception that children with disabilities are not able to tell their stories clearly and are easily confused.

In many countries, legislation does not recognize the testimony of children with disabilities and the law does not allow them to sign their names in legal documents or to give evidence under oath. There is a conspiracy of silence and widespread impunity surrounding these incidents of violence (UN Violence against children, 2023).

Lack of access to education

From an educational point of view, children with disabilities are more likely to miss out on school than other children. Even if they go to school, they are more likely to leave before finishing their primary education. According to the World Health Organization and the World Bank, in some countries “being disabled more than doubles the chance of never enrolling in school” and in fact, an estimated one in three out-of-school children have a disability (Their world, 2023).

Throughout Africa, less than 10 percent of children with a disability are in primary education. In some countries, only 13 percent receive any form of education. In Bangladesh, 30 percent of people with disabilities have completed primary school, compared to 48 percent of those without disabilities. In Zambia, it is 43 percent compared to 57 percent and in Paraguay 56 percent to 72 percent. According to one estimate, 75 percent of children with disabilities in Afghanistan are out of school. Many of them have been injured by land mines (Their world, 2023).

In developing countries, people with disabilities tend to be poorer than other adults. Missing out on education not only affects the quality of life for individuals and their families, but it also has a negative economic impact for countries. A study by the International Labour Organization found that countries lose between 3 percent and 7 percent of Gross Domestic Product by excluding people with disabilities from the job market. Education can help people with disabilities get increased access to employment, health and other services, and develop a better awareness of their rights (Their world, 2023).

Taking on a new perspective on disability

Children with disabilities often work hard to accommodate themselves to an inaccessible world that excludes them. But they are not problems that need to be fixed or changed (UNICEF, 2023). On the other hand, it is upon the community to include them and to enable them to fully participate in the society. The extent to which children with disabilities are able to function, participate in society and lead fulfilling lives depends on the extent to which they are accommodated and included (UNICEF, 2023).

When it comes to disability, children with disabilities are defined by and judged by what they lack rather than what they have (Save the Children, 2009). In order to contrast this narrative, some researchers started to employ a different word related to disability in order to adopt a different perspective: diversability.

The term diversability embraces the uniqueness and potential in every human being and the purpose of this term is to rebrand the word ‘disability’ to “democratize disability visibility, representation, and access”. People with disabilities can do the same day-to-day tasks as people without disabilities (Diversability, 2023). They may just approach them differently (Ramsey, 2021).

Living with a disability makes you more mindful. Functional limitations manifest in the life cycle of every one of us. The extent to which children with disabilities are able to lead happy lives depends on our own willingness to confront barriers to change (UNICEF, 2023).

Written by Arianna Braga

Internally proofread by Aditi Partha

Last updated on July 14, 2023

References:

Article 7 (2023). Article 7 – Children with disabilities. Retrieved from UN DESA at https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of- people-with-disabilities/article-7-children-with-disabilities.html, accessed on 9 July 2023.

Diversability (2023). Diversability: a movement. Retrieved from Diversability Inc. at https://www.diversabilityinc.org/#diversabilitymovement, accessed on 14 July 2023.

General Comment No.9 (2006). General Comment No.9 – The rights of children with disabilities. Retrieved from OHCHR at https://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/crc/docs/gc9_en.doc, accessed on 9 July 2023.

Otufat-Shamsi, S. (2015). Developmental Disabilities in Children Across Different Cultures. Retrieved from World forgotten children at https://www.worldforgottenchildren.org/blog/developmental-disabilities-in-children-across-different-cultures/22, accessed on 9 July 2023.

Ramsey (2021). What Does “Diversability” Mean?. Retrieved from Disability Associates at https://disabilityassociates.com/what-does-diversability-mean/, accessed on 14 July 2023.

Save the Children (2009). See me, Hear me: A guide to using the UN Convention on the Rights of people with Disabilities to promote the rights of children. Retrieved from Save the Children at https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/document/see-me-hear-me-guide-using-un-convention-rights- people-disabilities-promote-rights-children/, accessed on 9 July 2023.

Their world (2023). Children with disabilities. Retrieved from Their world at https://theirworld.org/resources/children-with-disabilities/, accessed on 9 July 2023.

UN DESA (2023). Convention On The Rights Of people With Disabilities (CRPD). Retrieved from UN DESA at https://social.desa.un.org/issues/disability/crpd/convention-on-the-rights-of- people-with-disabilities-crpd, accessed on 9 July 2023.

UN Violence against children (2023). Children with Disabilities. Retrieved from UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Violence Against Children at https://violenceagainstchildren.un.org/content/children-disabilities, accessed on 9 July 2023.

UNICEF (2021). Seen, Counted, Included: Using data to shed light on the well-being of children with disabilities. Retrieved from UNICEF at https://seotest.buzz/resources/children-with-disabilities-report-2021/, accessed on 9 July 2023.

UNICEF (2023). Children with disabilities. Retrieved from UNICEF at https://www.unicef.org/disabilities, accessed on 9 July 2023.