Children of Nauru

Realizing Children’s Rights in Nauru

If children’s rights are quite well respected in the world’s smallest republic, the Nauruan government would do well to ratify international treaties in order to further protect children’s rights, given that they are generally the first victims of global warming and of a shaky economy that is dependent on outside aid.

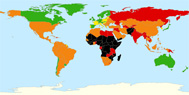

Orange level : Noticeable problems Population: 9.400 Life expectancy: 79 years |

Main problems faced by children in Nauru:

Right to an identity

The Nauruan child acquires his or her nationality by blood on the mother’s side. He or she is also automatically considered to belong to his or her mother’s tribe. On the other hand, the child of a Nauruan father and a foreign mother must ask for permission to be registered as a Nauruan.

Given this situation, some children are therefore at risk of being born stateless if the law of the mother’s country obliges her to lose her nationality upon marriage.

All babies are registered at birth or within the 21 days that follow in a government register under the name of the mother’s community. If they fail to be registered, the child loses his or her right to Nauruan nationality and the attendant rights, such as the right to property, for example.

Health

Health

In 2010, the mortality rate of children under 5 years was 40%, with 27% of newborns having a low birth weight and 24% of 0-5 year olds suffering from slow or retarded growth rates.

This is surprising when one considers the progress that has been made in modern medicine. Effectively, the health services are now divided between health care services and prevention services (first measure health care), with some doctors providing free consultations in hospitals.

In addition to this, the “Well-Baby Clinic”, specialised in children’s healthcare, visits different districts around the island once a week, notably to carry out health checks for children and to conduct vaccination campaigns. Despite the checks carried out, not all children are up to date in their vaccinations by the time they reach one year of age. The Health Department carries out further follow up checks once children begin school.

The Nauru government also provides free access to contraception, pre-natal, obstetrics and post-partum health care. Pre-natal and infant health services are operated bi-monthly in the hospital.

As for student health care, medical teams visit schools working to foster healthy habits concerning hygiene, dental care, first aid and the environment. These services however tend to be more and more insufficient and poorly coordinated.

In Nauru, a child’s sight and hearing are not tested until a problem presents itself in the affected child’s schooling. Prevention programmes (for sight, hearing and dental) do not exist.

Finally, childhood nutrition has become a major problem as the country prospered during the phosphorus mining period, which in turn caused significant changes in the typical Nauruan diet. Originally the island’s diet was comprised of fish, vegetables, fruits and coconut, however the diet of Nauruan children has now become very rich in sugar, salt and fat thanks to soft drinks and fast food.

Today, this phenomenon is exacerbated by the fact that these foodstuffs (fruit and vegetables) are very expensive (between 6-7 dollars per kilo for tomatoes, apples, oranges…) as the island is highly dependent on imports. Consequently, 75% of the population is touched by obesity and Type II diabetes has become very widespread.

Education

School is obligatory in Nauru for children aged 6 to 16. Public schools subsidise the cost of schooling and provide free school buses whilst parents take on the costs of school uniforms, excursions and the required materials.

In this small country, there are four early-age schools for children 3 to 5 years of age, three primary schools for 6 to 13 year olds, two secondary schools (one public school and one private catholic school) and also a school for handicaped children.

In this small country, there are four early-age schools for children 3 to 5 years of age, three primary schools for 6 to 13 year olds, two secondary schools (one public school and one private catholic school) and also a school for handicaped children.

Some children are sent to study in Australia or in New Zealand, particularly the children of parents who themselves followed secondary schooling abroad. The government offers some scholarships for these international students.

Even though education makes up an important part of the state budget, this sector still lacks crucial funding. As such, schools often lack access to drinking water or suffer from frequent cuts in water due to hydraulic water pressure problems or due to the lack of a pump. Health inspectors carry out checks on water quality, sanitary installations and other essential facilities and can order the closure of some schools. Unfortunately, due to a lack of funds, schools sometimes reopen without the problem having been rectified (due to the cost of maintenance, the cost of hydraulic pumps, school building renovation costs…). The level of training of school teachers is equally problematic.

Children and work

The minimum age before a child can work in Nauru is 17 and it is illegal to employ children under the age of 16. In spite of this, it appears that numerous children work in small family businesses from the the age of 14. Given that the majority of government checks on child labour take place mainly in the public sector, precise statistics on underage workers and on the proportion of children out of school are hard to come by.

Adoption

Adoption, whether formal or informal, is relatively common. Under the Nauruan laws, children can only be adopted by Nauruans, and vice-versa.

Even though children are culturally and legally dependent on their mother and her family, the paternal community also takes care of the child. It is not a rare occurrence for Nauruan children to be adopted by members of their own family.

Discrimination and disabled people

There are no anti-discrimination laws in Nauru nor any State agencies charged to protect the rights of disabled people. We note however, very few reported cases of discrimination against handicapped children.

They have access to health care, as stated in Article 24 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CROC). In addition to this, since 2009 the government has launched a handicapped policy with the target of installing wheelchair access ramps in public buildings.

Handicapped children also have access to education, in line with Article 28 of the CROC. Nauru has a special school dedicated to handicapped children, which brings together around a dozen children and three teachers. It is also possible for teachers to give classes or lead activities at home for small groups of handicapped children.

Nevertheless, not all children are able to attend school regularly due to transportation issues. Teachers are not well trained and, despite government efforts, school infrastructure remains relatively inaccessible for handicapped children. Such children benefit more from daily attention and care than from an adapted teaching program.

Drinking water

Most houses in Nauru are constructed with modern sanitation systems (flushing toilet, bathroom with running water).

However, problems of water supply and the maintenance of water pipes have a direct impact on the quality of life and of a household’s sanitary conditions. For example, malfunctioning running-water sanitary installations actually pose a greater health risk than pit toilets.

Moreover, the island of Nauru is highly dependent on water treatment and electricity supply because of a limited system of lakes and rivers. This is why, when there are power blackouts, the population has no access to water – or even if it has reserves, it is not possible for them to boil it: which in turn augments the risk of sanitary problems and generates an increase in child diarrhea.

In order to improve access to drinking water and to reduce its dependence on electricity, Nauru received US $4 million in January 2012 from the Pacific Environment Community (PEC) Fund for the installation of a sea water desalination factory and a solar energy system.

Environment

Environment

Numerous shipwrecks and pieces of rusty or sheet metal are strewn across Nauru’s shoreline and constitute a real danger for children swimming. In the same way, abandoned cars found across the island have turned into children’s playgrounds and pose a risk to their safety and security.

Abuse and violence towards children

In Nauru, statistics gathered on violence and abuse of minors is almost nonexistant. However, we note that there are a few cases of legal action taken in relation to violence or child abuse. In 2004, domestic violence and aggression towards children (men and women below 17 years) represented 1.1% of Nauru’s crimes.

Prostitution and sexual exploitation

In Nauru, the legal minimum age of sexual consent is 17 years. The laws concerning sexual abuse are also very strict. The punishment for an adult having sexual relations with a minor can rise to life imprisonment, especially if the child is less than 14.

Prostitution is illegal in Nauru and there is no report that mentions this type of offence. There are however some cases of transactional sexual relations, such as sexual relations between minors in exchange for food, clothing, etc.

Corporal punishment

Corporal punishment against children using a “reasonable” force is legal in Nauru (Section 280 of the penal code) as long as the punishment is given by a parent or relative, a person under whose authority the child is placed, or by a teacher or school head master. There is no stipulation as to the location in which this punishment can take place: house, all educational infrastructure, private and public places, health centres, etc. The punishment must always be used as a disciplinary measure.

Finally, hospitals rarely denounce domestic violence on children when they present for treatment.

Justice for minors

In Nauru, there is only one prison that has a detention facility for minors. Within this facility, corporal punishments are authorised by the law as a disciplinary measure. Torture and inhumane and degrading treatment however, are prohibited under Article 7 of the Constitution.

Realization of Children’s Rights Index

Realization of Children’s Rights Index