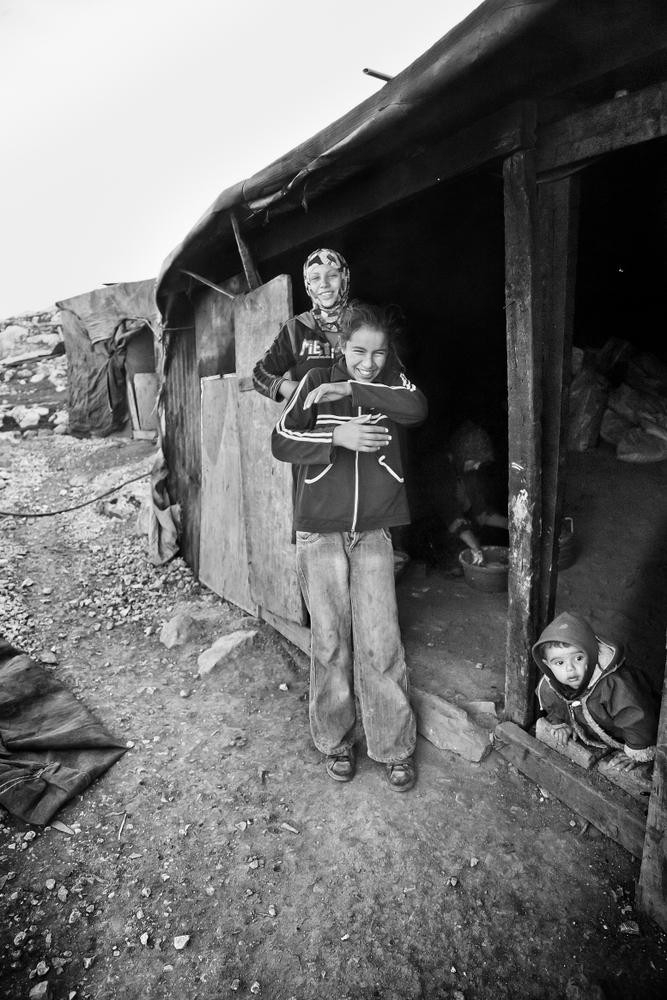

For the first time, Humanium is presenting a series of chronicles. They aim to take us to the heart of Palestine using four themes, four views, each one shining a different light on a region that is as beautiful as it is disturbing.

In the face of the endless divisions between Israelis and Palestinians, how can we imagine a peaceful future, when Palestinian society is itself divided and the Israeli world is made up of such diverse trends? Without going into the political debates that divide Palestinians, it is striking to note the social gap that separates men and women in the West Bank.

In Hebron, the most conservative city in Palestine, the climate can be quite oppressive, especially for a European. And that is without even considering the regular clashes that occur in the Old City and the endless discussions about the conflict. Despite the warm welcome of its inhabitants, you very quickly sense the weight of social rules and taboos.

For a young man, it immediately seems very difficult to meet women. However, I did have the opportunity to meet Salima*, a student at the University of Hebron, who enabled me to learn about the local student world and understand the social context better. “Here, boys and girls are separated very early on, and have virtually no opportunity to learn how to live together,” she says. “However, at university, the classes are mixed, which gives rise to embarrassing situations. When looking for a seat in the auditorium, boys don’t dare sit next to a girl because they are frightened of being considered a seducer. Conversely, girls avoid sitting next to a boy for fear of appearing interested.”

This means that the university can become a place of desire simply because it allows young people to meet. For this reason, anyone who wants to get in is strictly monitored by guards to stop anyone who isn’t a student from entering. So, waiting for Salima and her friends at the gate of the University gave me the disagreeable impression of being an intruder, a voyeur. You can quickly sense how this atmosphere could become suffocating and guilt-creating.

In Palestinian society, families pay special attention to their children’s education, which explains why it has one of the highest school enrolment rates is in the Middle East. In fact, 95.4% of Palestinian children were enrolled in primary school in 2018 (UNICEF, n.d.), with girls having just as much access to basic education as boys (Cardwell, 2018).

However, the gap widens with the level of study, and not in the way you might expect (UN Women). By the age of 15, 25% of boys had left school, whereas this is the case for only 7% of girls (UNICEF, 2018). It is therefore not surprising that women represent more than half (57% in 2012) of Palestinians taking part in higher education (UN Women).

Yet this does not mean that they subsequently obtain jobs that match their qualifications. Some examples from daily life clearly demonstrate this, such as the day when I was waiting to be served in a shop selling baklava, the traditional pastry of the peoples of the former Ottoman Empire. The server, having diligently filled the box as requested by the customer in front of me, then threw it to the cashier without any consideration. When my turn to pay came, I started a conversation with her and found she had a very good level of English, unlike her male colleagues, who speak only Arabic. The reason was simple: she had a Master’s degree in her back pocket. That didn’t prevent her from being shown so little respect in a job that undervalued her skills.

“It is a society for men”, said Reem*, a Muslim friend from Bethlehem, indignantly. Yet this mixed town, where Christians and Muslims rub shoulders, is a real breath of fresh air in comparison to Hebron. Muslim women dressed in modern clothes and without the hijab are a common sight, reducing the apparent distance that separates European society from their own. That is not necessarily to say that the lives of young women are much simpler there.

“Here, boys have the right to have a girlfriend and to say so openly, but girls don’t have the right to have a boyfriend!” Spot the inconsistency! “The only thing I want is to be able to hold his hand without having to hide it, that’s all,” she continues in reference to her beloved.

Relationships between men and women are not only complicated during youth, when there is not yet any commitment. “Men, once married, no longer respect their wives. They go crazy, paranoid. They claim that, because wives show themselves to their husband without a veil, nothing prevents them from removing the veil for someone else. They live in constant fear of being deceived”, Marah* asserts. A descendant of Bedouins, she grew up and lives in Aqabat Jabr, neighbouring Jericho. “Men don’t understand that if we let them see our hair and our body, it’s because we love them,” she says sadly. “It’s the gift of our love.”

A practising Muslim who wears the hijab, Marah sees herself as a feminist. In the face of this attitude on the part of men, she does not know whether she will one day marry, having lost hope of meeting someone who will love her for who she is. However, she still dreams of having children. In the meantime, she expresses her maternal feelings through her nephews and nieces, as well as through her pupils at the school where she teaches English.

Having visited the city one evening with one of her sisters, I asked her whether she was bothered about us being seen together in the street, especially after sunset. In fact, it isn’t common for a woman to find herself alone in public with a man, even less so when it comes to smoking shisha in a café.

However, like Marah, she can handle whatever others might say about her. It doesn’t bother her; she knows who she is and remains faithful to her upbringing and faith. Having grown up without a father and living with their elderly mother and sisters, Marah and her sisters have been able to retain a great deal of freedom.

However, the West Bank, like Israel, is full of contrasts between the various cities and the multiple communities. Some women, originally from Hebron and covered by the hijab in their home town, become “liberated” women in Ramallah. The administrative capital of the West Bank is seen as a place of emancipation. There are bistros serving alcohol, there is dancing, and there is partying. Women feel free to wear the veil or not: they are not looked at like they are in Hebron.

For the young people who came here to study, this change opens a door. Some of them take advantage of it to go on dates, and some women take advantage of it to meet Europeans, with whom they feel freer. Some of them even dare to call themselves atheists, radically cutting themselves off from their traditional upbringing.

Yet these apparent freedoms are not representative of Palestinian society, much less of the mentalities of the city of Hebron. One day, the conversation of a group of men around me turned to women. Some did not hesitate to say that women are less important than men. Seeking to avoid a debate that would be too aggressive, I asked how they could say such a thing. How could they say that one person is more or less important than another? Then, as in all the discussions that lead to an impasse, my interlocutors came out with the ultimate argument: “It’s in the Koran!”

During my stay, I often heard this unanswerable argument, in the widest variety of discussions, and sometimes even to justify totally opposing opinions. Everyone uses it to their advantage, but don’t ask which verse of the sacred book it comes from. “And if the Koran had been revealed to a woman?” I dared to ask. Then, against all odds, my question resulted in silence, and the men continued their meals without saying a word.

The situation of women in the Muslim world and in traditional Arab societies is a delicate subject. As Europeans, we tend to want to apply our standards and vision of progress and freedom to them. However, these ideals, inherited from the Age of Enlightenment, may not apply to a culture so different from our own. Every evolution takes place within a context and that of the Arab world is often caught between modernity and tradition.

We cannot ignore the fact that a region exposed to such a strong cultural mix and to a situation of conflict can only evolve by following its own rhythm. That is without forgetting the communities of Eastern Christians, whose reality is even more different and too often ignored. In fact, Palestinian society is undergoing considerable change. Despite the tensions that the conflict with Israel breeds, you can sense that young people want to forge ahead and move faster than we might think.

The education of children can be powerful lever toward a new conception of interpersonal relationships. It is not rare to see young Palestinians who express a great desire to see their world open up. Rather than wait until they match us, let’s encourage them to advance along to their own path, toward a harmonious society that knows how to merge faith, new realities and traditions.

* An assumed name

Written by Alexis Baron

Translated by Sharon Rees

Proofread by Holly-Anne Whyte

References

Cardwell, L. (2018, June 21). The State of Girl’s Education in Palestine. Retrieved October 8, 2019, from The Borgen Project: https://borgenproject.org/the-state-of-girls-education-in-palestine/

UN Women. (n.d.). Gender in education: From access to equality.

UNICEF. (2018, July 26). Nearly 25 per cent of boys aged 15 out of school in the State of Palestine. Retrieved October 8, 2019, from UNICEF: https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/nearly-25-cent-boys-aged-15-out-school-state-palestine

UNICEF. (n.d.). Education and adolescents. Retrieved October 8, 2019, from UNICEF: https://www.unicef.org/sop/what-we-do/education-and-adolescents

Further information:

https://palestine.unwomen.org/en

https://www.cidse.org/advocating-for-women-rights-in-palestine/