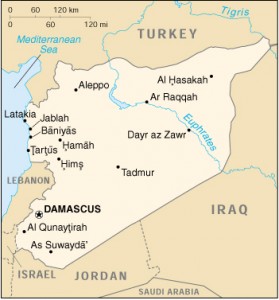

Children of Syria

Realizing Children’s Rights in Syria

Before the start of the civil war in March 2011, Syria was a middle-income country that was able to adequately provide for its people. The continuing crisis in Syria has left over 470,000 people dead (Syrian Center for Policy Research, 2016), including over 12,000 children, and over 7.6 million internally displaced. UNICEF estimates that 8.4 million children are affected by the conflict either in Syria or as refugees. Moreover, 6 million Syrian children are in need of humanitarian aid, and more than 2 million do not have access to it as they live in areas difficult to reach or under siege.

Population: 22,4 million Life expectancy: 55,7 years |

Main problems faced by children in Syria:

In armed conflict, children are often deliberately targeted or not protected adequately — or both. The lives of Syrian children have been greatly affected by the conflict. Every day numerous violations of children’s rights take place in areas such as health, education, protection, etc. Syrian children are regularly exposed to escalating violence and explosive weapon attacks. Some are forced to become child soldiers while others are pushed into the workforce to provide for their families. Several thousand have lost family members and have been forced to flee their homes, only to become displaced within Syria or in neighbouring countries. Others still have made the precarious journey — often alone — across the Mediterranean to make their way to Europe.

The crisis has led to limited livelihood opportunities and plunged several million Syrians into poverty. Both in Syria and its neighbouring countries, Syrian children have been forced to become breadwinners in their families. Education systems have come under attack in Syria, as armed groups tend to see the targeting of schools, schoolchildren, and teachers as military strategy. In addition, sexual violence against civilian populations has been characteristic of the Syrian conflict. Fear of such violence, which increases when perpetrators are not held accountable for their actions, has a debilitating effect on vulnerable populations. It can restrict the mobility of girls and women and can result in their staying at home and avoiding school.

Moreover, the war in Syria is characterized by multiple humanitarian law violations. In specific, the current situation goes against humanitarian law that forbids direct or indiscriminate attacks on civilians, the destruction of hospitals, and requires all parties to the conflict to grant access to humanitarian aid. There are also numerous human rights violations amounting to war crimes or crimes against humanity.

In 2015, UNICEF identified 1500 individual cases of grave violations of children’s rights in Syria, among which over 60% were cases of murders and maiming following the use of explosive weapons in inhabited civilian areas. Moreover, children are also victims of repression by the regime. In 2014, the UN revealed that the syrian regime detained and tortured children.

Syria had a strong education system in place before the civil war, with almost 100% primary school enrolment and 70% of children attending secondary school. According to the 2004 census, Syria’s literacy rate was 79.6%: 86% of men and 73.6% of women were literate. In 2002, education was made compulsory and free from grades 1 to 9. In 2016, UNICEF reports that 2.1 million children in Syria and 700 000 Syrian refugee children do not have access to education. In 2016, there was a total of 80,000 children refugees in Jordan that were out-of-school (HRW).

Deliberate destruction of education facilities is a long-standing feature of armed conflict. Schools can be seen as embodying state authority; therefore, they are seen as a legitimate military target by non-state actors. Syria has been heavily affected by attacks on education, including attacks on students, teachers, and buildings, targeted killings, and abductions. Since the start of the conflict, over a quarter of Syrian schools have been damaged, destroyed, or are being used as shelters by Internally Displaced People (IDPs). Such targeted attacks have a profound impact on children and education. Even a single attack may result in forced closures of schools and displacement of populations. Moreover, even when schools remain open, children may be afraid to travel to school, fearing attacks, kidnappings, or other threats. In addition, the school system is also hampered by teachers fleeing the war. In 2015, UNICEF identified 1,500 cases of grave violations of children’s rights in Syria. A third of the children among the 1,500 cases, were killed while at school, or travelling to or from school. Moreover, the violence and trauma of war also affects their mental development and their ability to learn.

With no end in sight to the conflict, there are fears that the crisis will lead to a ‘lost generation’ of children, who will lack basic necessities and will be unable to gain access to education.

UNICEF estimates that around 7 million children in Syria live in conditions of poverty.

International trade sanctions, imposed since the anti-regime protests began in March 2011, have had a significant negative impact on the socio-economic situation of the civilian population. The sanctions have limited the state’s revenue, which has limited the resources available to pay salaries in the public sector. This, in turn, has caused significant income reduction in several families.

Furthermore, these sanctions are partially responsible for the increased price level of basic commodities. This has greatly increased the pressures on families who spend the largest proportion of their income on basic commodities. In 2015, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Food Program, 9,8 million Syrians suffer from food insecurity.

According to Syrian domestic law, it is illegal to employ minors before they either complete their basic education or reach the age of 15 years of age — whichever comes first. Child labour was an issue in Syria prior to the war, but the humanitarian crisis that ensued has exacerbated the problem. Whether in Syria or in neighbouring countries, children are now forced to work in conditions that are mentally, physically, and socially dangerous environments.

In Syria, children may be sent away from their families to other parts of the country or to neighbouring countries to generate income, avoid being recruited, or avoid being injured in the conflict. Families that struggle to meet their basic needs are sometimes forced to put their children out to work, marry their daughters early, or allow their children to be recruited by armed groups. Children work in agriculture, metal work, carpentry, restaurants, as well as sell items on the street, wash cars, collect trash, or even beg.

In Syria, children (most of them boys) are forcibly recruited and used as soldiers by all parties of the conflict, often without the consent of their parents, and half of them being under the age of 15 years old. These children play an active part in the fighting and can be used to kill, sometimes being assigned tasks that endanger their lives.

For refugee children, the situation is equally dire. In 2015, according to the UN, 70% of syrian refugees in Lebanon lived below the poverty line. In 2016, in Jordan, 90% of syrian refugees live under the poverty line, and 67% of families have contracted a debt (UNHCR). Since adult refugees are largely unable to work in the formal labour market in neighbouring countries, they are forced to rely on the informal sector, at the risk of being imprisoned, fined, or deported back to Syria. In such a desperate situation, they are forced to turn to their children for help. It is difficult to estimate the number of syrian children refugees who work, because, among other reasons, families and employers hide the problem by fear of the consequences, but a report of UNICEF and Save the Children states that in 2015, between 13 and 34% of children between 7 and 17 years old work in the Za’atari refugee camp in Jordan.

There has been around 1 million people injured since the beginning of the war according to the WHO in 2015.

Until the start of the conflict, Syria’s child survival statistics matched those of other middle-income countries; however, unremitting violence has resulted in a shattered healthcare system that has left millions of children suffering. Children in Syria are not just dying as a result of indiscriminate attacks on populated areas, but also because they do not have access to basic medical care.

According to the WHO, in 2015, more than half the hospitals and public health centres were either partially functioning because of a shortage of staff, medicines or due to damage of the buildings, or closed down. More than 15,000 of Syria’s 30,000 doctors have fled the country, according to Physicians for Human Rights. Medical staff and patients, including children, regularly come under attack—both en route and inside hospitals; limited access to basic healthcare facilities has forced people to resort to turning homes into makeshift hospitals.

Before the conflict, 96% of women in Syria had medical assistance; today, in some sub-districts, less than a quarter have regular access to reproductive health services. Vaccine programmes in Syria had a coverage rate of 91% before 2011, falling to 68% in 2012. Although there are no current reliable statistics, the rate is likely to be much lower today. Diseases that were previously eradicated in Syria, such as polio, now affect up to 80,000 children across the country. In 2016, Save the Children counted 200 000 deaths from chronic diseases because of a lack of access to treatment.

Sexual violence and child marriage

Under Article 34 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), children are protected against all forms of sexual abuse. Minors are further protected against sexual abuse under Syrian domestic law (Article 489).

Sexual violence against men, women, boys, and girls has been a characteristic of the Syrian civil war. The UN Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict (SRSG-SVC) states that sexualised gender violence has been reported in the context of detention, at checkpoints, and during house-searches in Syria. Female refugees in neighbouring countries have cited fear of rape as a major factor that led to their decision to leave Syria. Since 2014, there has been an increase in the number of reported cases of sexual violence perpetuated by terrorist groups, in particular ISIL. In August 2014, ISIL abducted hundreds of Yazidi women and girls from Sinjar, in northern Iraq. Some of these women and girls were taken to Syria and sold into sexual slavery.

Child marriage in Syria existed before the war, but at a much lower rate than today. It has increased dramatically since the start of the war; in some cases, such as in Syrian refugee communities in Jordan, the rate of child marriage has doubled since 2011. The minimum age for marriage under Syria’s Personal Status Code (1957) is 18 years for boys and 17 years for girls.

Although Syria ratified the CRC in 1993, there were general reservations to provisions that were not in conformity with Syrian and Islamic Law. For example, Article 16(2) of the CRC prohibits State parties from permitting or giving validity to a marriage between persons who have not attained their majority; even so, a marriage of underage children can be authorized in Syria, with consent of a father or grandfather. For girls the minimum age is then 13, and for boys, 15. Unfortunately, a large number of marriages of minors are arranged by families and are against the girl’s wishes. These marriages often have serious health consequences for young girls — often married off to much older men — who are not aware of the risks involved, from sexual exploitation to reproductive and sexual health issues. Under Syrian and Islamic law, polygamy is legal; it is common in rural Syria, and in some settings, has increased since the start of the conflict.

There are several reasons why Syrian families resort to child marriage for their daughters in refugee and IDP communities. IDPs in Syria and refugees in neighbouring Arab countries face constant food and economic insecurity and lack livelihood opportunities. The girls and women in these communities are at an increased risk of sexual violence. In Za’atari camp, female refugees have reported that they fear being pressed into sham marriages. In Bekaa Valley, Lebanon, gangs are reported to be exploiting refugee women and children. Under pressures to protect their female children and ease the pressure on family resources, families may resort to child marriage. Further, under Syrian law, a rapist may avoid punishment by marrying his victim, and marital rape is not explicitly criminalised.

The Syrian Nationality Act, which denies Syrian women the right to pass on their nationality to their children, has devastating impacts on the civil, economic, and social rights of Syrian children. Children of marriages between Syrian women and foreign spouses cannot access free education or inherit property, and have limited access to health care services and other benefits available to Syrian nationals.

Additionally, Syrian laws can have an adverse impact on minorities in the country. In 1962, the passing of the Legislative Decree No. 93 led to 120,000 Syrian Kurds being stripped of their nationality, as they were unable to prove that they had been living in Syria since 1945. This minority group, which constitutes the second largest ethnic group after Syrian Arabs in Syria, is effectively stateless. They cannot make use of resources and services available to Syrians, such as food subsidies, admission to public hospitals, and employment at government agencies. Further, marriages between Syrian citizens and Kurds are not legally recognised; children born from these unions are also stateless. Kurds with foreign status are not issued passports: they are not legally allowed to leave or enter the country. This adversely affects Syrian Kurdish refugee families who have fled to Kurdistan in northern Iraq.

Stateless children in Syria lack civil documentation, which does not allow them to access state services, including health care facilities, educational institutions, and judicial support. As a result these children are extremely vulnerable to food insecurity, marginalisation, sexual exploitation, trafficking, labour, displacement, and forced marriages.

Written by : Priyanka Sinha