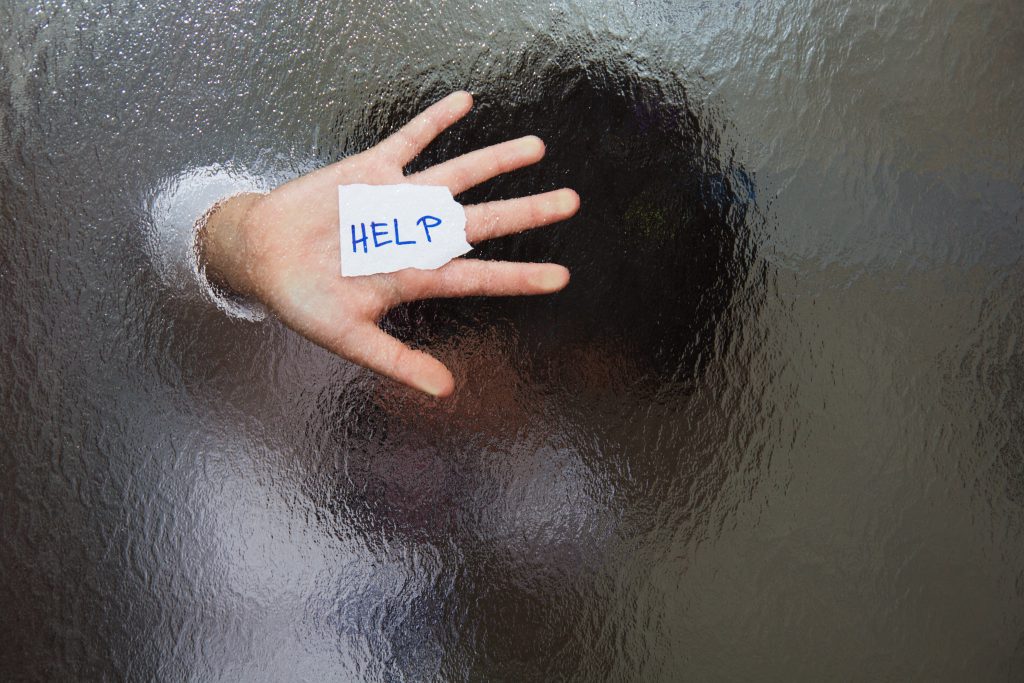

With the lockdown of millions of families, many children found themselves stuck at home with violent parents without the opportunity to ask for help. The isolation and the stressful atmosphere of the pandemic sometimes acted as a catalyser and some parents who usually were non-violent, had abusive behaviours. Whether it is psychological or physical violence, this kind of behaviour should never happen, and a child should be protected and safe under any circumstance, otherwise it can lead to negative effects both in the short- and the long-term.

Isolation is a Key Component of Domestic Violence against Children

#EntendonsLeurCris [‘HearTheirCries’]. This hashtag came from a campaign launched by UNICEF France and ‘NousToutes’, a French collective, to alert people about violence against children during the lockdown period of the Covid-19 pandemic. With the different lockdown measures, the rates of domestic violence increased, as this reality happened everywhere around the world.

Staying at home for days and weeks, for many children, meant being trapped and watched at all times by their parents and became dangerous. For a number of them who were already suffering from violence by a family member in their everyday lives, asking for help had been even more difficult, being unable to speak to another adult or even make a phone call freely.

Besides the recurring cases, the context of the pandemic increased the severity of domestic violence. Indeed, the anxiety related to a job loss, a fall in income, or the inability to take a break and take time for oneself, could foster resorting to violence against children, equally by parents that were previously violent and non-violent.

Violence in All its Forms

But what is violence? It can be an isolated act or several acts, creating a cycle of abuse. It can occur at all ages. There are several types of violence but here this article focuses mainly on psychological and physical interpersonal domestic violence, happening at home. This could be corporal punishment, or equally denigration, relentless criticism… Harassment or violence between young people are, for example, excluded as they come from a group outside the home.

For a long time, violence was accepted as an educational tool towards children. In addition to the recurring cases of violent parents, there is a more subtle and insidious violence, which is not necessarily thought of: psychological and mental violence. Denigrating, humiliating, arguing and raising your voice to your children, instead of explaining why their behaviour is not socially acceptable… All of these behaviours have negative effects.

When we put ourselves at the level of the child, who does not have the same perception of an environment and the same self-control as an adult, these are extreme reactions. And yet, while initiatives have been beneficial in banning and preventing violence against children, such practices continue, as shown by the news published on UNICEF’s website on the subject.

Violence stems from numerous causes and influences. According to the ecological model (that is, taking all the levels of influence: individual, relational, community, social), several risk factors exist and can affect all households. Children exposed to violence will tend to reproduce this pattern when they grow up. The poorest households are most affected by violence, living in disadvantaged neighbourhoods therefore means being more exposed to violence and aggravating factors such as alcohol and drugs.

But beyond the situation of families and the community, society can also promote social norms that normalise violence. Moreover, public policies, if they do not reduce economic, social and gender inequalities, do not help prevent situations of violence in the most at-risk households.

Immediate Effects and Long-Term Repercussions

So yes, physical and psychological violence should be prohibited. But why? Why is spanking not a solution? Why is shouting at your child, at any age, not recommended? The brain of a child does not react in the same way as an adult. It is still developing. It has been scientifically proven that violence creates high levels of cortisol, the stress hormone, which has a negative impact on brain development. During a moment of violence, children will have to deal with several emotions, notably stress, shame and sadness, and the injuries they might have due to physical abuse.

Obviously, an isolated act of abuse will have little effect in the long-term, but it can set a precedent. The more children are subjected to violence, the more they will secrete these hormones. Too much of them can be harmful for children’s development and this will have an effect on the adult they will become. In addition, it has been proven that witnessing domestic violence by children will have the same repercussions on children’s development and health as if they themselves had been the target of violence.

The Need to Change Customs

The long-term effects can be different, depending on the exposure to violence, both in terms of duration and intensity, and the age of the child. But the effects of violence must not be minimised. Asking yourself about the way you educate your children is the best way to progress and avoid harmful situations. Since violence is multifactorial, it deserves an equal reaction. The WHO’s “INSPIRE” model is interesting in this regard.

Indeed, it proposes to target all strata of society to limit violence. Their seven-strategy program built on the grounds of the International Convention on the Rights of the Child, offers initiatives with legislative, administrative, social, and educational measures.

For example, this program offers training to parents on positive and non-violent disciplines and the importance of communication. It also focuses on strengthening child-protection mechanisms at the community level. All sectors and ecological levels of society are thus encouraged to banish violence against children.

Since 2014, Humanium has been working with local parents and leaders in Rwanda to raise awareness about children’s rights and the importance of their roles as adults, to make them acknowledge the dangers of violence. Deeply invested in the protection of children, Humanium also organises free online workshops for childcare professionals from all countries and backgrounds. If you are interested in participating in one of these workshops, don’t hesitate to get in touch with josie.thum@humanium.org. You will be most welcome!

Written by Juliette Bail

Translated by Anna Carthy

Proofread by Suzanne Corpet

Bibliography:

Bouzouina, L. (2007, 3). Concentrations spatiales des populations à faible revenu, entre polarisation et mixité: Une analyse de trois grandes aires urbaines françaises. Pensée plurielle(16), pp. 59-72.

Fortin, A. (2009). L’enfant exposé à la violence conjugale : quelles difficultés et quels besoins d’aide ? Empan, 73(1), pp. 119-127.

Iamarene-Djerbal, D. (2017). De la violence sur enfants. NAQD(53), pp. 27-47.

Thielland, J.-P. (2018). Violence éducative : quelles conséquences sur le développement psychologique des enfants ? Le Journal des psychologues, 1(353), pp. 73-77. Récupéré sur Le Journal des psychologues.