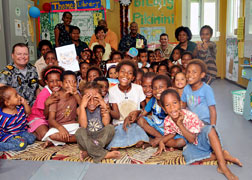

Children of Papua New Guinea

Realizing Children’s Rights in Papua New Guinea

The situation of Papua New Guinean children is truly difficult. Despite certain improvements, especially in justice and education, huge gaps persist in terms of the protection of children’s rights. Children are the principal victims of abuse, exploitation, and failures of the health-care system.

Population: 7,3 M Life expectancy: 62,4 years |

Main problems faced by children in Papua New Guinea:

With 37% of the population living beneath the international poverty threshold, (US $1.25/day) many children in Papua New Guinea lack access to drinking water and appropriate nourishment. 28% of children are moderately or severely malnourished, and 43% suffer a delay in growth. Poverty is also one of the principal causes of trafficking, exploitation, child labor, and lack of schooling in the country.

With 37% of the population living beneath the international poverty threshold, (US $1.25/day) many children in Papua New Guinea lack access to drinking water and appropriate nourishment. 28% of children are moderately or severely malnourished, and 43% suffer a delay in growth. Poverty is also one of the principal causes of trafficking, exploitation, child labor, and lack of schooling in the country.

Corporal punishment as a means of education is not forbidden by the law. Parents, tutors, and teachers often resort to violence to discipline their children. These children are also very often the victims of negligence and abuse, particularly sexual, in everyday life, at home and at school.

In addition, acts of physical violence towards women and girls are ubiquitous and even considered “normal” by a large portion of the population. Thus, more than half of them have already been attacked by a man. Many, even among young couples, have been beaten by their partner, and the risk of being attacked outside of one’s home is also very high. The lack of criminal proceedings against the perpetrators of such violence encourages criminals. This is all the more so because the forces of order, reputed for their brutality, would themselves be guilty of numerous acts of violence, including sexual, against young women.

In addition, acts of physical violence towards women and girls are ubiquitous and even considered “normal” by a large portion of the population. Thus, more than half of them have already been attacked by a man. Many, even among young couples, have been beaten by their partner, and the risk of being attacked outside of one’s home is also very high. The lack of criminal proceedings against the perpetrators of such violence encourages criminals. This is all the more so because the forces of order, reputed for their brutality, would themselves be guilty of numerous acts of violence, including sexual, against young women.

Child witches

Barbarous acts of torture and murders of people accused of witchcraft, often young women and girls, have been reported. Around fifty murders were perpetrated in 2010 in the provinces of the Eastern Highlands and Chimbu. The figures indicate that the number of victims is rising, while the government does nothing to prevent these assassinations or to punish the guilty parties.

The capacity of the country’s health-care system and basic health education are insufficient. The system of free care put in place by the government some years ago is in abandon, as the allocated budget is very weak and the infrastructure is degrading. Spurred by unfavorable climactic and environmental conditions, there are frequent epidemics of dengue fever, malaria, and hepatitis A, and the rates of maternal and infant mortality are very high, especially in rural regions. One out of 21 children fails to live past the age of 5.

The capacity of the country’s health-care system and basic health education are insufficient. The system of free care put in place by the government some years ago is in abandon, as the allocated budget is very weak and the infrastructure is degrading. Spurred by unfavorable climactic and environmental conditions, there are frequent epidemics of dengue fever, malaria, and hepatitis A, and the rates of maternal and infant mortality are very high, especially in rural regions. One out of 21 children fails to live past the age of 5.

The country also holds the sad record of having the highest rate of contamination by HIV/AIDS in the region. More than 1% of the population is infected, according to the WHO. Poor access to tests, treatments, and means of prevention, and the harassment of the sick and of persons possessing contraceptives encourages the transmission of the disease.

Women are more exposed to infection because they are subjected to sexual aggression and inequalities in treatment. They represent 60% of the diseased and the rate of contamination among girls ages 15-19 is the highest in the country, four times greater than that of men of the same age.

In addition, the United Nations estimated that 5,610 children were orphaned due to HIV/AIDS in 2009, and that 3,000 children were contaminated.

Education is not obligatory, and it is free only for the first two years of primary school. Because of the lack of money or complex family situations, many children have little or no access to it. Some attend school very late, which often leads to scholastic failure. As a consequence, more than 30% of youth ages 15-24 are illiterate.

Education is not obligatory, and it is free only for the first two years of primary school. Because of the lack of money or complex family situations, many children have little or no access to it. Some attend school very late, which often leads to scholastic failure. As a consequence, more than 30% of youth ages 15-24 are illiterate.

Children living in rural regions are more subject to a lack of schooling. Less than 50% of them go to school and only half finish the primary level. Girls are less likely to receive complete schooling, notably being the victims of sexual abuse at school or on the path leading towards it.

The minimum legal age of marriage is 16 years old for girls and 18 years for boys, but it can be lowered respectively to 14 and 16 with permission from parents and the court. However, in rural communities where traditional marriages are practiced, it is not rare for children to marry even earlier, sometimes by the age of 12.

These premature marriages have particularly weighty consequences for girls, of whom 15% between the ages of 15-19 are already married or engaged, notably endangering their health and education. The practice of a “bridal price,” (a form of dowry), polygamy, and forced marriages are all sources of violence and discrimination. Young girls are also often given in marriage to pay familial debts, and they thereby find themselves exploited.

Child trafficking and exploitation

While it signed the Convention on the worst forms of child labor, Papua New Guinea has taken insufficient preventative measures to protect children from trafficking. Only sexual exploitation was forbidden by the treaty, and only for girls. Child trafficking in the aim of labor exploitation is therefore not illegal. In all cases, the traffickers are rarely pursued, and even more rarely punished.

Child exploitation, including dangerous work, is very widespread. Very few measures have been taken to confront this phenomenon and to protect victims. As such, even though the legislation makes provisions for heavy punishments in cases of sexual relations with a minor, and child pornography is illegal, prostitution of young girls, at times from the age of 10, has become a significant means of economic survival.

Child exploitation, including dangerous work, is very widespread. Very few measures have been taken to confront this phenomenon and to protect victims. As such, even though the legislation makes provisions for heavy punishments in cases of sexual relations with a minor, and child pornography is illegal, prostitution of young girls, at times from the age of 10, has become a significant means of economic survival.

It is not rare for the parents themselves to participate in the exploitation of their children, renting them like servants or prostitutes when they don’t have the means to provide for them. A widespread practice consists of having one’s child “adopted” in an informal manner by a richer member of the family or by a well-off family, often as payment for a debt. The child thereby finds him or herself in a situation of slavery, obligated to work for hours, without rest, free time, care, or education.

Domestic violence, the collapse of the family, parent unemployment, the rural exodus, and pressure from friends are the principal factors leading children to live and/or work on the street.

Today, street children are numerous on the streets of the capital and around the work sites of miners and foresters, selling cigarettes, CDs, or food, even though the law forbids making minors younger than 16 work (except in certain circumstances and as long as it does not interrupt their education). The majority of them have never been to school or left very early. The government is working on the development of a national effort to fight against this phenomenon, but for the moment, no concrete actions have been carried out.

Poverty, the rural exodus, and the collapse of the family unit are to blame for the growth of misdemeanors committed by minors. They are responsible for 10% of the criminal acts in the capital. No fewer than 40% of youth, particularly boys between 14 and 18 years old, find themselves in conflict with the law.

The judicial system has recently been reinforced by the addition of a law related to infractions and sexual crimes against minors, and of another relating to the protection of childhood (Lukautim Pikinini). However, progress is slow and much effort remains to be made. The age of criminal offense remains fixed at 7 years old, a limit that is much too low.

The majority of youths are called out for small crimes and see themselves refused of their fundamental rights, especially access to health-care. Many find themselves violently mistreated by the national police, whose abuses of power are notorious, particularly towards delinquents, prostitutes, or homosexual minors.

Since the establishment of juvenile courts, juvenile delinquents have been separated from the traditional judicial system. However, arrested youths are still too often placed in prisons with adults, where they face significant risks of being attacked. Conditions of detention are equally inappropriate for children, particularly concerning hygiene and health-care.

Expropriations

Certain unscrupulous natural-resource exploitation companies do not hesitate to employ force to dislodge communities living in exploitation zones, without offering any financial aid. Destruction of villages, gang rapes, and other violations of human rights have been reported. Because of the lack of regulation from the government, the brutality of these expropriations as well as the uprooting and the destitution which follows have grave consequences for children.

Certain unscrupulous natural-resource exploitation companies do not hesitate to employ force to dislodge communities living in exploitation zones, without offering any financial aid. Destruction of villages, gang rapes, and other violations of human rights have been reported. Because of the lack of regulation from the government, the brutality of these expropriations as well as the uprooting and the destitution which follows have grave consequences for children.

Social discrimination persists towards girls and certain groups of vulnerable children. This is the case, for example, for disabled children or those born out of wedlock. Moreover, the country’s constitution does not forbid discrimination based on handicaps.

Girls and women, notably in rural and isolated communities, are particularly affected by certain discriminatory customs concerning marriage, its dissolution, and relations within the family, especially regarding questions of inheritance.