Taking an introspective look at humanitarian action’s pitfalls throughout the 2010s is key for the constant betterment and no-repeat of past mistakes that must, without question, unfold within the sector in the new decade. Our turning into the new year provides an invaluable opportunity to also turn the page, and to honestly attest to humanitarianism’s key failings in order to, between us, ensure that humanitarian work continues to make positive impact without harm.

Doing better for children in the new decade

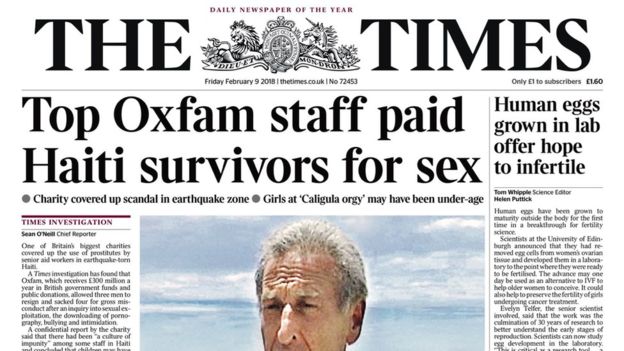

The past decade has, most notably and most appallingly, witnessed the revelation of extensive sexual violence and exploitation exacted by the aid industry on the people it purports to help. With internal inquiries dating back to 2001 and over 40 major organisations implicated, the scale of systemic abuse is astonishing, prolonged and well-known by the sector itself (Ainsworth, 2018).

Some of the biggest names in humanitarian work including Oxfam, Save the Children, Red Cross, Médecins Sans Frontières, International Rescue Committee and Care International were implicated in these ‘scandals’ which reveal a deep-rooted abusive culture in the aid industry. Oxfam was, once again, implicated in ‘aid for sex’ (or, rape) as late as 2019 (Times, 2019).

These persisting issues are inexcusable and affect children disproportionately. This cannot be allowed to continue. By acknowledging the most grave failures we are better enabled to address and thwart them with concrete policy change and action. ‘Do No Harm’ – a cornerstone of humanitarian principals – must unequivocally be translated into reality for the first time in the 2020s.

The widening humanitarian wage gap

One of the inequalities that persists in the humanitarian sector is that of the growing wage gap between international (often Western) and national staff (nationals in the country of operation). In a 2016 study and audio documentary by Anna Strempel focusing on India, China, Malawi, Uganda, Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea, it was found that local staff are paid on average four times less than international staff – in spite of having similar levels of education and experience.

“When you are local, you’re not paid equally to international employees, and that determines where you will live, what type of car you use, how you are able to enhance your own security.”

– Salome Nduta, Protection officer at the National Coalition of Human Rights Defenders of Kenya (Pauletto, 2018).

Franz – a humanitarian professional with 11 years of experience, and an Indonesian national – has an international manager who earns over 10 times more than he does. Franz has 12 days leave a year and his counterpart a month, as well as a better insurance package. A wage gap of 2 to 3 times is, by some, considered justified, but in reality the gap ranges from 4 to 15 times the wage of national staff counterparts (Strempel, 2016).

On top of this staggering economic inequality scaffolded by humanitarian organisations, international staff often receive generous ‘packages’ as part of their contracts that national staff do not, and which are not taken into account by the wage gap. These packages can include payment of their children’s private school fees, a company car, generous personal and medical insurance coverage, increased annual leave and paid-for bills and accommodation.

This has massive bearings on the quality of life of national staff working in the humanitarian sector as well as on their families and wider communities. Shockingly, 80% of local humanitarian workers said that their pay was not sufficient to meet their everyday needs (Strempel, 2016), and a 2017 UNOCHA study affirmed that international staff receive greater psychosocial support, training and security provisions than their national counterparts (UNOCHA, 2017).

So, a sector supposedly promoting human rights and equality, is in fact contributing to the perpetuation of inequality and poverty. A culture of silence around the wage gap exists within organisations as national staff on lower salaries are subject to a power relationship with their international colleagues, and the international colleagues who in turn profit handsomely from their position, are quick to justify the disparity and not about to argue themselves out of a comfortable benefits package and salary… even if they are sincerely motivated by justice and equality for all. This culture of taboo makes the conversation even more essential.

The great cost of devaluing national workers

“Many perceive aid work as these Westerners swashbuckling around the world, but the real aid work is being done by Bangladeshis in Bangladesh, Jordanians in Jordan, and so on.”

– Thomas Arcaro, Professor of sociology at Elon University (Pauletto, 2018)

The economic and material inequality between humanitarian staff is also to some extent reflected in the tangible safety disparity. About 80% of humanitarian workers who are killed, seriously wounded or kidnapped on the job are national staff (New Humanitarian, 2017), and the 2018 Aid Worker Security Report showed that this lethal proportion is on the rise (UNOCHA, 2018).

One such case of violence against aid workers in South Sudan highlights the manifestation of aid worker inequalities. A report from the Feinstein International Centre shows that following the high-profile 2016 subjugation of a group of female humanitarian aid workers to sexual violence in Juba, South Sudan, women who were international staff were immediately evacuated from the country and provided with physical, psychosocial and emotional healthcare, as well as being put on indefinite sick leave.

The Sudanese staff members however – who had survived the same assault – were left in Juba ‘without access to the necessary medicine to prevent pregnancies, HIV, STDs or other diseases’ with the report declaring it ‘unclear’ what support they were provided, if any, and suggesting that it is likely they would be expected to rely on themselves and local health care services since resident staff have different packages. It asserts that national staff are ‘often disadvantaged in the care they receive’ (Mazurana, 2017); the impact of such ‘disadvantage’ being in some cases devastating upon the health, wellbeing and safety of the people concerned.

Overturning tired tropes and dangerous rhetoric

Many humanitarian organisations continue to subscribe to discriminatory rhetoric, narratives and behaviour. Indeed, a Humanitarian Women’s Network survey found that 69% of women had experienced discrimination, harassment or abuse at work (The New Humanitarian, 2017), and there is persistent racism still present within the sector, whose neocolonial qualities remain far too prominent (Jayawickrama, 2018).

For example, marketing and fundraising initiatives premised on poverty porn and white-washed western images and narratives of white saviourism – the white western aid worker protagonist coming to the rescue of the passive vulnerable black or brown ‘beneficiary’ – was near-standard during the 2010s, heavily promulgating damaging racist stereotypes (Al Jazeera, 2019). The 2010s have been years of education and a sharp learning curve for the sector.

These issues have been highlighted repeatedly and the coming years provide the invaluable opportunity for the industry to demonstrate what it has learnt – as well as to continue the much-needed and invaluable work it is carrying out, except – crucially – without any of the harmful by-products.

This article in no way provides an exhaustive overview of humanitarian failings, of which there are many. It does, however, spotlight some examples of key areas in the most urgent need for change and improvement. Learning from our past and not repeating the darkest moments of our history as a sector is paramount to achieving our ultimate humane mission and objective. Taboos which persist around these most difficult topics must be broken again and again.

We are accountable to primarily ourselves, and our responsibility to uphold this accountability is paramount. We must look with hope and optimism to the decade ahead. Humanitarian work has had a wealth of successes and accomplishments. By building upon the positive change being carried out, whilst quashing damage being done, humanitarian action may continue to build a better planet in the 2020s for the children of the future.

Written by Josie Thum

References

GARCÍA-MINGO Elisa, ‘Cuando los cuerpos hablan. La corporalidad en las narraciones sobre la violencia sexual en las guerras de la República Democrática del Congo’ in Revista de Dialectología y Tradiciones Populares, vol 70. (1) (Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 2015).

SIMPSON Laura, Christine Goyer and Manuel Sanchez Montero, ‘Roundtable: Do No Harm’ given at Intensive Programme (Warsaw: The University of Warsaw and Network on Humanitarian Action (NOHA), 07.09.2018).

SECRET AID WORKER, ‘Who will save the white saviours from themselves?’ (London: The Guardian, 2016), accessed 11.01.2020.