Realizing Children’s Rights in Swaziland

Roughly 100,000 children in Eswatini are orphans and grow up without their parents. Due to HIV/AIDS and high levels of poverty, the phenomenon of children raising children is quite common (Swaziland, n.d.). Moreover, this means they are often deprived of health services and miss out on a decent education.

Realization of Children’s Rights Index: 6,07 / 10

Red level: Difficult situation

Population: 1.13 million

Pop. ages 0-14: 37.8%

Life expectancy: 57 years

Under-5 mortality rate: 49.4‰

Eswatini at a glance

Eswatini, officially the Kingdom of Eswatini, is a landlocked country in the eastern flank of South Africa, where it borders Mozambique. In the colonial era as a protectorate, and later as an independent country, Eswatini was known as Swaziland, however, the name of the country officially changed in April 2018. An uncodified Swazi Law and Custom, which is recognized both constitutionally and judicially, regulates traditional administration and culture. The national language is siSwati, though it shares official status with English, which is generally used for official written communication.

Eswatini has a very young population, with more than one-third under the age of 15 and almost one-third between 15 and 29 years of age. Life expectancy is higher for women than for men, but the average for both is about 57 years, much lower than the global average. The lower life expectancy and population growth rate and the higher-than-average death rate are in part due to the prevalence of HIV/AIDS in the adult population (Britannica, 2021).

Status of children’s rights

The Kingdom of Eswatini ratified the UNCRC 1989 on 7 September 1995 (United Nations Human Rights Treaty Bodies, 2021). Eswatini has also ratified key international children’s rights treaties, which aim to protect children from abuse and exploitation. These include the Optional Protocols on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography and on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict (ratified on the 24 September 2012) (Ibid). Both optional protocols address a substantive area related to the UNCRC 1989, although, like most countries, Eswatini has yet to ratify the Optional Protocol on Communication Procedure 2011 (Child Rights Connect, 2021).

From a regional perspective, the Kingdom of Eswatini ratified the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child 1990 (ACRWC) on 5 October 2012 (African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, 2021). Additionally, the country is progressively moving forward in protecting children’s labor rights by ratifying fundamental International Labor Laws such as the International Labor Organization’s (ILO) Convention 138 on Minimum Age 1973 (No.138) and the Convention 182 on the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labor 1999 (No.182) in 2002 (International Labour Organization, 2021).

The rights of the child are covered under Section 29 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Swaziland 2005 (World Intellectual Property Rights, 2021). This section ensures that all children remain protected from child labor by reaffirming the importance of their right to health, education and development 29 (1). The country has also enacted comprehensive protective legislation for children in the Children’s Protection and Welfare Act 2012 (African Child Policy Forum, 2021; CPWA 2012). This legislation seeks to provide protection for children from abuse and to promote their welfare.

Over and above this legislation, the country has a policy that illustrates its prioritization of the protection and promotion of children’s rights, in particular vulnerable children (Child Rights International Network, 2016). The Government has also made significant strides in policy and legislative reform in addressing the challenges of gender-based violence by enacting the Sexual Offences and Domestic Violence Act 2018 (Swaziland Government Gazette Extraordinary, 2018); SODVA 2018).

Addressing the needs of children[1]

Right to health

HIV/AIDS has had a devastating impact on Eswatini. Heterosexual sex is the main mode of transmission, accounting for 94% of all new infections (UNAIDS, Swaziland Global AIDS response progress, 2014). The epidemic is widespread and affects all populations, although certain groups such as sex workers, adolescent girls, young women and men who have sex with men are more affected than others (AVERT, 2020). In 2018, 23,000 young people (aged 15-24) were living with HIV in Eswatini (UNAIDS, AIDS info, 2020). This age group is more likely to have low testing, treatment and viral suppression rates, and HIV-related stigma continues to affect prevention and treatment efforts. Between 2010 and 2014, this stigma increased by over 20% and only one in four adolescents had accepting attitudes towards people living with HIV (UNICEF, 2021).

Early sexual debut and high levels of intergenerational sex between young women and older men is also driving HIV transmission among this age group. New infections among children, as well as AIDS-related deaths have reduced greatly to fewer than 1,000 each year. However, the HIV epidemic continues to have a significant effect on children in other ways, as around 45,000 zero- to seventeen-year-olds are orphans due to AIDS-related illnesses (UNAIDS, AIDS info, 2020).

Poor health and poverty are inextricably linked. Among under-five child deaths, 27% occur during the first month of a child’s life, arising from problems such as premature birth, asphyxia, infection and congenital disorders. Childhood pneumonia and diarrhea also contribute to 12% and 10% of under-five deaths respectively. Regional disparities exist with under-five mortality, with the highest rates in the Lubombo and Manzini regions. Limited access to quality health education and health care, along with weak integration of essential services, impact negatively on health outcomes in Eswatini. The chance of children born to uneducated mothers not living beyond their fifth birthday is three times higher than for children born to mothers with tertiary education (UNICEF, 2021).

Right to water and sanitation

Clean water, basic toilets and good hygiene practices are essential for the survival of children in Eswatini. Water and sanitation-related diseases are one of the leading causes of death for children under five years of age (UNICEF, 2021). Some 40% of children have been identified as being deprived of access to safe water and 20% to adequate sanitation. The situation is complicated by significant inequalities: 90% of people in the wealthiest quintile have access to an improved water source against 10% for the poorest (UNICEF, 2015).

In 2017, the Ministry of Education reported that 11% of schools in Eswatini did not have access to a water supply and of those with a water supply, 80% had access to safe water and 20% had an undefined water source. Of the available toilets in schools, 43% are for girls, 44% are for boys, and 12% are mixed (UNICEF, 2021).

Sanitation standards deteriorate as one moves from urban areas to pre-urban areas and finally to rural areas. The Poverty Reduction Strategy and Action Plan asserts that only 45% in rural areas have proper sanitation facilities. While 63% of households in urban areas use flush-toilets, the rest use either pit latrines or bushes (Ministry of Natural Resources and Energy, 2018). Safe drinking water helps to reduce water-borne diseases, reduces public and private expenditure on health care, and further increases productivity as time spent by women and children travelling to collect water is reduced.

According to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) targets, in order to achieve universal access to sanitation by 2030, Eswatini needs to improve, replace or build about 400,000 improved household sanitation facilities, or about 30,000 facilities per year (Ministry of Health, 2019). Despite the low percentage of basic sanitation service coverage, and the intensive support provided by the Ministry of Health to increase rural sanitation coverage, households remain the country’s largest financiers of sanitation devoting substantial resources to developing their own facilities.

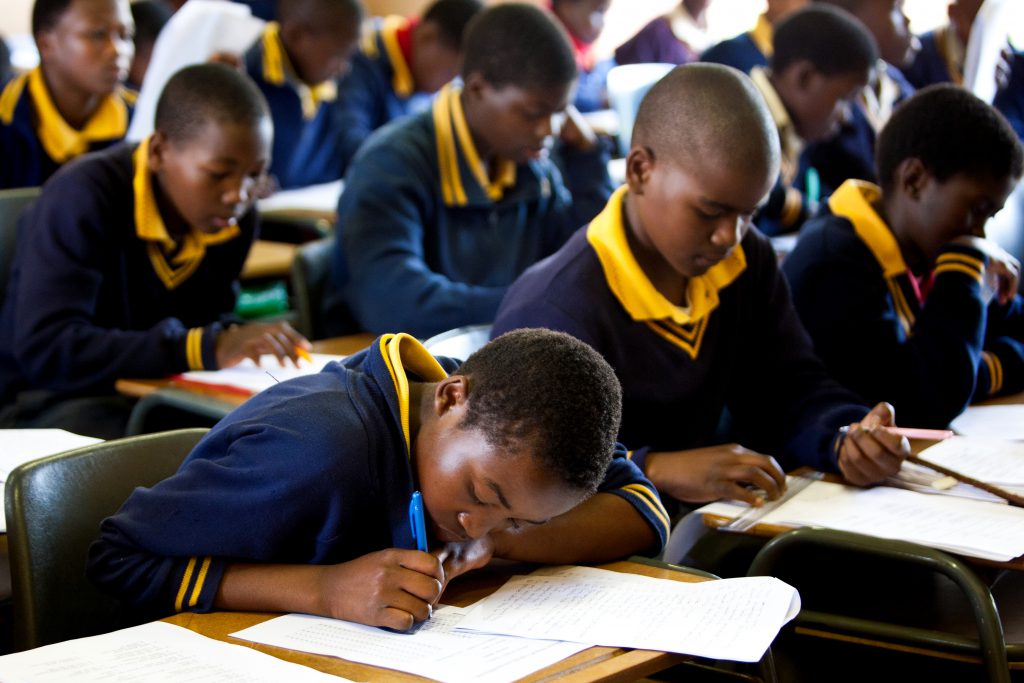

Right to education

The law requires that children complete primary school, and parents who do not ensure their children’s completion of primary education are fined for noncompliance. Education is tuition-free through grade seven. The Office of the Deputy Prime Minister receives an annual budget allocation to pay school fees for orphans and other vulnerable children (OVC) in both primary and secondary school. Seventy percent of children are classified as OVC.

In 2003, the Ministry noted that poverty, hunger and severe drought resulted in high levels of school dropouts (Eswatini, n.d.). Consistently low enrolment rates in secondary schools remain an issue for educational attainment and development skills. In Eswatini, income and gender-based inequalities further keep many adolescents and young people from achieving a better future and empowered livelihoods (UNICEF, n.d.). Nevertheless, the Government has ensured Free Primary Education (FPE) for all Eswatini children as per the Constitution and the Free Education Act 2012 (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2017).

The FPE programme was designed to remove barriers and increase access to primary education for all school-going-aged children. It provides relevant quality education and eliminates all forms of disparities and irregularities in primary education. It is aimed to eradicate illiteracy and to equip every child with basic skills and knowledge in an endeavor to alleviate poverty. This is in line with Section 29(6) of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Swaziland 2005, which guarantees the right to free primary education in public schools (World Intellectual Property Rights, 2021).

FPE was successfully rolled out from grades 1–2 in 2010; by 2015, it was extended to grade 7. The enrollment rate has increased from 231,555 in 2009 to 239,422 in 2012 and 247,717 in 2015. Indicators suggest that Eswatini is on track to achieve universal access to primary education specified in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (United Nations Development Programme, 2021). However, improvement of access is but one aspect of the process, as there is still a need to ensure that all children complete their primary education.

Completion rates at primary levels suggest that repetition and dropout might still be pushing some children out of the system. In 2006/2007 the completion rate was at about 59.3%, and in 2012 it increased to 76.4%, suggesting that more children stayed to complete primary education. This is an improvement, which implies that more children are being retained by the system (Child Rights International Network, 2016).

Right to identity

Under Eswatini law, mothers are not permitted to confer their citizenship to their children. Eswatini’s Constitution stipulates that any child born inside or outside Eswatini prior to 2005 to at least one Eswatini parent acquires citizenship by descent. However, children born after 2005 only acquire Eswatini citizenship from their fathers, unless the birth occurs outside marriage and the father does not claim paternity, in which case the child acquires the mother’s citizenship.

Birth on the country’s territory does not convey citizenship. If a Swati woman marries a foreign man, even if he is a naturalized Swati citizen, their children carry the father’s birth citizenship. The law also mandates compulsory registration of births. According to the 2014 Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey, 50% of children younger than five were registered, and 30% had birth certificates. Lack of birth registration may result in denial of public services, including access to education (State, 2019).

The Births, Marriages and Deaths Registration Act No.5 (1983) stipulates registration of births (National Legislative Bodies / National Authorities, 1983). Furthermore, children’s rights to a name and nationality are protected by the Constitution of the Kingdom of Swaziland 2005 and CPWA 2012. This ensures that children can derive their nationality, not only from their father, but also from their mothers unless the child is born outside of marriage and is not adopted or claimed by the father (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2017).

Despite these legislative measures, the country still faces challenges with registration, such as some parents not holding identity documents, which are required for the registration of children’s births. Furthermore, caregivers often do not see the value in getting identity documents and birth certificates. Some parents even prefer to obtain South African citizenship and cannot then register their children as Eswatini citizens because the law prohibits dual citizenship and customary naming practices, which require family consultation or naming ceremonies before they can name and register the child’s birth (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2017).

Risk factors → Country-specific challenges

Girls’ rights and gender-based violence (GBV)

In Eswatini, gender-based violence is a common challenge faced by women and girls, as 1 in 3 females have experienced some form of sexual abuse by the age of 18, and 48% of women have reported having experienced sexual abuse in their lifetime (UNFPA, n.d.). Victims of violence often suffer sexual and reproductive health consequences, including forced and unwanted pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections including HIV, and even death. In addition, the 2016 National Study on the Drivers of Violence against Children in Swaziland (NSD VACS) confirmed that gender inequality and entrenched social and community norms such as ‘Tibi Tendlu’, or family secrets, prevent disclosure of physical, sexual and emotional abuse.

One staggering statistic to emerge from the data revealed that for every girl child known to Social Welfare as having experienced sexual violence, there are an estimated 400 girls who have never received help or assistance for sexual violence (Fry, 2016). The Government has attempted to rectify the situation by enacting the SODVA 2018, however, a lack of implementation and poor budgeting has resulted in the shortcomings of this legislative instrument (Swaziland Government Gazette Extraordinary, 2018). Moreover, GBV has only increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Child labor and exploitation

In 2014, 69,980 Eswatini children were working in agriculture forestry and fishing which represent the main sectors of the economy (ILO, 2014). Children are also victims of sex trafficking and domestic labor. In 2019, Eswatini made an effort to eliminate the worst forms of child labor, as the Government approved and formally launched an Action Plan to sentence and arrest individuals who engage children in forced labor and sex trafficking.

However, as of today, Eswatini does not have any legislation regulating labor conditions, and minimum age protections do not extend to children engaged in domestic and agriculture work, which does not conform to international standards that require children to be protected by the minimum age to work (Labor, 2019). This is despite signing and ratifying key international labor conventions such as No.182 and No.138 (International Labour Organization, 2021).

Child trafficking and abduction

Eswatini faces a considerable prevalence of trafficking of children, especially girls, mainly because of the high numbers of orphans and the effects of HIV/AIDS. Swati girls, especially orphans, are at risk of sex trafficking and domestic servitude. Legal protection has been strengthened by two key laws: the provisions in the CPWA 2012 which domesticates The Hague Convention, and the People Trafficking and People Smuggling (Prohibition) Act of 2009 (Government of Swaziland, 2010).

This means that children are protected against illicit transfers and trafficking, and the legislation also prescribes penalties of up to 20 years for the trafficking of adults, and a higher penalty of 25 years for trafficking children. Given the trans-national nature of the problem, the government has cooperated with other member states of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) to develop victim identification guidelines as well as a national referral mechanism.

The country has ratified key international instruments, which include the 2012 Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, which supplements the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (United Nations, 2000).

Environmental challenges

Eswatini, like many countries in Africa, has contributed minimally to Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions in the atmosphere, and yet, it faces some of the worst consequences and generally has a very low capacity to cope with the impacts of climate change. Eswatini is highly vulnerable and exposed to the impacts of climate change due to its socio-economic and environmental context. Furthermore, climate variability, including the increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, disproportionately affects the poor. Climate change also has adverse effects on water, food, fuel, health, education and access to social services (Ministry of Tourism and Environmental Affairs, 2016).

Moreover, although normative and policy frameworks have been developed to address climate change and disaster risk reduction issues, they have not yet been fully implemented. Consequently, some communities, especially those in the country’s drought-affected Southern region, experience food and nutrition insecurity (United Nations Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework (UNSDCF), 2020).

Written by Ginevra Vigliani and Igi Nderi

Last updated on 24 March 2021

Bibliography:

African Child Policy Forum. (2021, March 2). Swaziland. Retrieved from Child Law Resources

AVERT. (2020). HIV and AIDS in Eswatini. Retrieved from AVERT

Britannica. (2021). Eswatini. Retrieved from Britannica

Eswatini, T. G. (n.d.). Primary education.

Labor, U. D. (2019). Eswatini Child Labor.

Macrotrends. (n.d.). Eswatini life expectancy

State, U. D. (2019). Country Reports on Human Rights Practices. Retrieved from Eswatini

Swaziland. (n.d.). Retrieved from SOS children’s villages

UNAIDS. (2014). Swaziland Global AIDS response progress

UNFPA. (n.d.). Gender based violence. Retrieved from Eswatini

UNICEF. (n.d.). Eswatini Education

UNICEF. (2019, June 01). Eswatini-Country Profile. Retrieved from Data UNICEF

UNICEF. (2021, March 5). Eswatini HIV/AIDS. Retrieved from UNICEF Eswatin

World Data Atlas . (2019, June 01). Eswatini – Population ages 0-14 . Retrieved from Knoema

Worldmeters. (n.d.). Swaziland population

[1] This article by no means purports to give a full or representative account of children’s rights in Eswatini; indeed, one of the many challenges is the scant updated information on children, much of which is unreliable, not representative, outdated or simply non-existent.