Realizing Children’s Rights in Burundi

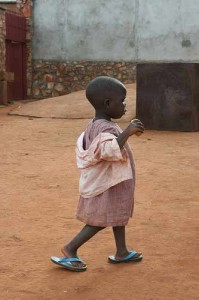

Children in Burundi are often unable to enjoy fulfilment of their rights due to the difficult context in which they live. Children are vulnerable to serious risks which undermine their safeguarding including: child trafficking, poverty, environmental disaster and forced displacement.

Realization of Children’s Rights Index: 5,46 / 10

Black level: Very serious situation

Population: 11.8 million

Pop. ages 0-14: 45.5 %

Life expectancy: 57.50 years

Under-5 mortality rate: 58.5 ‰

Burundi at a Glance

Burundi is a small landlocked country just south-east of the African continent’s centre, with a high population density and an extreme susceptibility to the protracted global climate emergency. Burundi is one of the poorest countries in the world, and rain-fed agriculture employs around 90% of its inhabitants (UNDP, 2020). Child rights in Burundi unfold in a highly complex and difficult context of post-conflict, post-genocide, post-colonialism and the neoliberal international order. Many measures have been taken by the nation in recent years to improve Burundi’s child protection framework, but there remain prevalent day-to-day and structural challenges seriously impacting children’s lives.

People in Burundi experienced a crisis of violent civil and political unrest from 2015 to 2018, civil war from 1993 to 2005, and two genocides at the end of the 20th century. Moreover, the Kingdom of Burundi endured over 60 years of brutal European colonialism, and suffered a military German invasion in 1899, becoming part of colonial ‘German East Africa’, then ‘Ruanda-Urundi’ following military conquer and occupation by Belgium; only to gain independence in 1962. Europeans brought diseases that devastated the people of Burundi, as well as the plant and animal life they relied upon, leading to widespread famine.

Germany carried out genocide in ‘German East Africa’, using concentration camps, and scorched earth tactics to invoke mass starvation, amongst other crimes. Today, Burundi’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission is attempting to investigate such crimes (Sarkin-Hughes, 2011). Despite significant local resistance, Europe ruled Burundi ‘through’ the Tutsi monarchy, and oversaw creation of racial identity cards for residents, thus laying the groundwork of ethnic division before the genocides of 1972 and 1993.[1]

Status of Children’s Rights

In Burundi, there exists an established national legal framework for the protection of child rights, and Burundi has ratified key international treaties including the Child Rights Convention, and both of its Optional Protocols. Burundian law penalises commercial sexual exploitation of children with 10 to 15 years in prison and a fine, and penalises child pornography with 3 to 5 years in prison and fines. There were, however, no prosecutions of this nature during 2018. Furthermore, the law penalises violence against or abuse of children, with 3 to 5 years’ imprisonment (U.S. Department of State, 2018). Burundi’s 2014 anti-trafficking law criminalises forced labour and trafficking. There are, however, gaps in Burundi’s Penal and Labour Codes which leave some children without legal protection.

The minimum age for child labour (16 years old) does not apply to children who are informally employed, and the use of children in the production and trafficking of narcotics is not illegal. The use of children in armed conflict is prohibited by the constitution, but only criminalised if the child is under 15 years old, leaving children aged 15 to 18 vulnerable. There exist institutional mechanisms in Burundi for the enforcement of child labour laws, although enforcement agencies reportedly lack sufficient numbers of labor inspectors (Bureau of International Labour, 2017).

In Burundi child marriage and forced marriage is illegal, with the minimum age for sexual consent at 18. The Constitution’s article 29 legally prohibits same-sex marriage, and article 567 of Burundi’s Penal Code penalises consensual same-sex sexual relations between adults with up to 2 years prison, violating Burundian people’s right to privacy and non-discrimination (Human Rights Watch, 2018).

Addressing the Needs of Children

Right to education

In Burundi, since the government abolished school fees in 2012, education is free, compulsory, and universal from ages 7 to 13. Consequentially, primary schools saw a high 96% enrolment rate for the years 2010 to 2014, with an 89% youth literacy rate overall (UNICEF, 2016). Secondary school in Burundi, however, comes with tuition fees and is not compulsory, contributing to a low net enrolment ratio of 25%, and an even lower attendance rate between 2010 and 2014 (UNICEF, 2016). Challenges which can impede children’s access to education in Burundi include that throughout the country informal fees are imposed for schooling at all levels (U.S. Department of State, 2018), as well as costs of school books and school uniforms.

Furthermore, the requirement of birth certificates as a predicament for school attendance leave unregistered or undocumented children with reduced access to schooling and more vulnerable to child labour; with indigenous members of the Batwa ethnic group being particularly affected (Bureau of International Labour Affairs, 2017). Child refugees and children returning from forced displacement may not speak French or Kirundi, and face linguistic barriers to education. Such challenges must be seen in light of Burundi’s recent civil war which did great injury to education sector with many schools destroyed and children and teachers displaced.

Rights to health and water

Children in Burundi have access to free health care until the age of 5, securing a crucial aspect of their right to health during the most vulnerable period of infancy. The principal direct threats to Burundian children’s health include malaria, malnutrition and respiratory diseases. Burundi is also considered to be at risk of Ebola from neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo.

Almost half of all Burundian children live more than 30 minutes away from their closest health care facility, and about 80% of Burundian children are cited as living in accommodation using ‘non-improved combustibles’ which produce particle smoke, at once heightening the risk of respiratory diseases, and, potentially reducing the risk of malaria for those who do not have mosquito nets, because smoke can deter insects (Ramful et. al, 2017).

Reprehensibly, half of the children in Burundi suffer from stunting due to malnutrition (Save the Children, 2019). Unfortunately, the traditional cultural practice of removing an infant’s uvula (at the rear of the mouth) causes numerous infections and deaths, undermining some children’s right to health (U.S. Department of State, 2018). Access to safe drinking water is available for the majority of the population, but as of 2015 a quarter of people in Burundi still could not benefit from this crucial provision, threatening many children’s right to water (UNICEF, 2016).

Right to identity

In Burundi, birth registration is free of charge and undertaken by the government within the days that follow a child’s birth, ensuring a key aspect of their right to an identity.

The Burundian constitution states that children inherit citizenship from their parents. There remains, however, a significant portion of children whose births are not registered (75% of births were registered between 2008 and 2014 according to UNICEF), and these children may not have access to essential public services, including primary schooling and free medical care before the age of 5 (U.S. Department of State, 2018). Children whose births are not registered are unable to benefit from having an identity in the eyes of their society, and are often invisibilised and marginalised.

Rights to freedom of expression and opinion

There have been serious incidents of small-scale politically motivated arrests and imprisonment of children who peacefully exercise their basic human right to freedom of expression. These children’s right to freedom of expression has been violated. Six schoolgirls were arrested in 2019, accused of doodling on President Nkurunziza’s picture in their text books. A boy was also arrested and released that same day.

These girls were later released following scrutiny from international media and online pressure, but the charges against them were not dropped, and they may face up to five years in prison. Similarly, in 2016 dozens of children were detained for drawing on textbook images of the President (Nicholson, 2019). Children in Burundi can face serious punishment, then, for expression which is considered to be dissenting or critical, and their right to freedom of expression and freedom of opinion is thus curtailed.

Risk factors → Country-specific challenges

Environmental rights

The global climate emergency severely infringes upon Burundian children’s ability to enjoy their basic human rights. Government inaction on the climate emergency, particularly from top-emitting countries (including the USA, UK, China, France, Germany, Australia, Saudi Arabia and South Africa), impacts Burundian children’s rights to life, water, health and education (World Population Review, 2020).

Burundi is particularly affected, despite having the lowest greenhouse gas emissions on the planet, contributing just 0.01% of total emissions (Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2018). In 2020, 1.7 million Burundians were identified as in need of humanitarian assistance, 58 per cent of whom were children (OCHA, 2020). Burundi is one of the countries the most susceptible to climate change, and its inhabitants are regularly hit by recurring climate disasters at local and national levels, with life-altering consequences.

An astounding total of 1,586 natural disasters, mostly torrential rains, floods and high winds, were recorded in Burundi between October 2018 and December 2019, with impacts that included forced displacement, total or partial destruction of; crops, homes, classrooms, water networks and health centres (OCHA, 2020). These often cause severe localised emergencies, and are responsible for displacing almost 80% of the country’s 120,000 internally displaced people – most of whom are children. One example is the province of Kirundo, which faced a rain deficit between January and March 2019, worsening the already challenging situation of food insecurity and further impacting the nutritional status of children (UNICEF, 2019).

Child displacement

Burundi risks becoming a forgotten refugee crisis as, since 2015, hundreds of thousands of people fled the political crisis that erupted in the country, taking refuge in neighbouring countries such as Tanzania and Uganda. More than half of all refugees within Burundi are children, with over 30,000 children having been repatriated to Burundi since 2017, and over 78,000 children registered as internally displaced throughout the 18 provinces (this is decreasing) (UNICEF, 2019). Many displaced children are unaccompanied, and are at severe risk of abuse, neglect, sexual violence, exploitation and death (War Child, 2020).

Child refugees returning to Burundi frequently lack access to basic services and have been identified as highly vulnerable (Bureau of International Labour Affairs, 2017). Child displacement is linked to Burundi’s complex context and unrest, as well as to the protracted global climate emergency. The refugee situation in the country is now slowly improving (War Child, 2020).

Child poverty

Burundi consistently figures as amongst the few poorest countries in the world (USA Today, 2018). Child poverty is a persistent problem in Burundi, and worsened after the country’s 2015 crisis. In a 2016 report on child poverty, UNICEF identified 78% of Burundian children as living in poverty (monetary, and/or non-monetary poverty), with children who live in rural areas being particularly affected (Ramful et. al, 2017). Child poverty intersects with the other challenges to the fulfilment of child rights in Burundi. It is estimated that just under half a million children live in extreme poverty in the country, with indigenous children from the Batwa minority being disproportionately affected (Street Child, 2020).

Street children

According to the NGO War Child, thousands of children continue to live on streets throughout Burundi. These children rely on humanitarian assistance for basic services, such as medical care and economic assistance, since the government provides them with minimal support. Children who live or work on the street continue to face arrest and detention, and many were detained as part of a plan to end vagrancy. Although the government intended to reintegrate detained street children and adults to their places of origin, it seems this has not yet occurred.

Children who are homeless and live or work on streets also reportedly experience police brutality and theft of their possessions. The government established a commendable goal of having no children or adults living on the streets by the end of 2017, but did not achieve this, and street children are highly vulnerable to having their fundamental rights violated (War Child, 2020).

Child soldiers

The use of child soldiers appears to be very rare in Burundi, and is not a threat to the rights of most children in the county. There have been some incidents, though, including in 2015 when it was reported that about 58 children, some younger than 15, were recruited and forced to take part in an armed invasion against the government in Kayanza Province. Similarly, there are reports of hundreds of Burundian children who may be trafficking victims, including girls, being trained in weaponry at a camp in south Rwanda (Bureau of International Affairs, 2018). Efforts have been made by the Burundian government to demobilise former child soldiers and to reintegrate them into their communities, and the government does not recruit children into its armed forces (Bureau of International Affairs, 2018).

Child marriage

Forced marriage, and child marriage, is illegal in Burundi. National law protects children, setting the legal age for marriage at 18 for girls and 21 for boys, with the minimum age for consensual sex being 18. Rape of a minor (= sex with a minor) incurs 10 to 30 years’ imprisonment for perpetrators. Although child marriage was reported in southern muslim regions, this seems to be uncommon. Burundi’s Ministry of the Interior has made efforts to persuade Imams not to officiate illegal or unregulated marriages (U.S. Department of State, 2018). Nonetheless, 6% of girls in Burundi aged 15 to 19 are married, and 1 in 37 of them gives birth, indicating that child marriage and rape of girls are serious problems which threaten the lives and the wellbeing of many girls in Burundi (Save the Children, 2019).

Child trafficking and prostitution

Child trafficking in Burundi is a serious problem, although its prevalence is difficult to ascertain due to lack of data, and the invisibilised nature of its victims. Child trafficking intersects with other forms of abuse and rights violation such as child labour, exploitation and sexual violence. Traffickers exploit children in domestic servitude and child sex trafficking via prostitution. Child victims of these practises are all sexually assaulted, and are regularly unpaid, verbally abused, and even enslaved. Adults who offer children lodging can push these children into prostitution in order to pay for living expenses.

This results in the existence of child brothels which are located in certain impoverished areas of Bujumbura, near Lake Tanganyika, in Ngozi, Gitega, Rumonge and along trucking corridors (U.S. Department of State, 2019). Burundian girls, including orphaned girls, are also trafficked internationally for commercial sexual exploitation into Kenya, the Middle East, Rwanda, and Uganda. Equally, Burundian children are trafficked to Tanzania and are forced to labour in agriculture (Bureau of International Laboura Affairs, 2017).

Written by Josie Thum

Updated on 6 April 2020

References:

Bureau of International Labour Affairs (2018) Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labour – Burundi.

Bureau of International Labour Affairs (2017) ‘Burundi’, Ref World.

Human Rights Watch (2019) ‘Burundi Events of 2018’, Human Rights Watch Online.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands (2018) Climate Change Profile Burundi.

Ramful, Nesha, Liên Boon and Chris de Neubourg (2017) La Pauvreté des Enfants au Burundi, UNICEF.

Sarkin-Hughes, Jeremy (2011) Germany’s Genocide of the Herero: Kaiser Wilhelm II, His General, His Settlers, His Soldiers, Boydell & Brewer, ISBN 978-1847010322.

Save the Children (2019) ‘The Challenges for Children in Burundi’, Save the Children Online.

Street Child (2020) ‘Burundi’, Street Child Online.

UNDP (2020) ‘Burundi’, UNDP and Climate Change Adaption Online.

UNICEF (2019) ‘Burundi Humanitarian Situation Report, January-March 2019’, Relief Web.

UNICEF (2018) ‘Country Profiles: Burundi’, UNICEF Data.

UNICEF (2016) The State of the World’s Children 2016 statistical tables, UNICEF Data.

UN OCHA (2020) ‘Burundi Situation Report’, UN OCHA Online.

U.S. Department of State (2019) ‘2019 Trafficking in Persons Report: Burundi’.

U.S. Department of State (2018) ‘2018 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Burundi’.

War Child (2020) ‘Burundi’, War Child Online.

World Population review (2020) ‘CO2 Emissions by Country 2020’, World Population Review Online.

[1] This article by no means purports to give a full or representative account of children’s rights in Burundi, which are vast, complex and constantly changing. The article aims to highlight principal challenges to child rights in Burundi, and is not representative of Burundi’s rights history, innovations or achievements.